|

This is a long overdue article that I’ve been getting email requests for since 2015, and it seems like a good time to finally write it. For those of you who have been waiting with bated breath, I hope it lives up to your expectations. As for everyone else, I hope you find this informative and engaging, and as always my inbox is always open for questions. Enjoy! Sieves: What are they Sieves are rhythmic cells and/or longer rhythmic sequences created through basic filtering, mapping, and overlay procedures. They can be simple or quite complex depending on what your goals and working methods are. The concept of sieves is associated primarily with Greek composer/mathematician/architect/awesome dude Iannis Xenakis. My article here is not going to cover the specific processes that Xenakis used because, full disclosure, it’s more complicated math than my brain is able to explain in a simple way (let alone fully understand…), and I’ve found my own idiosyncratic ways to perform similar processes and get quality results. That said, if you’re interested in learning about Xenakis’ rhythmic sieves you can check out Xenakis’ own book Formalized Music (Pendragon Press, 1963…good luck finding this one), James Harley’s Xenakis: His Life In Music (Routledge, 2004) or for the Max/MSP-minded there’s this very nice video. Rhythm sieves are similar in concept to pitch sieves but different application in order to account for multiple degrees of variation

Another primary difference is that pitch sieves are a compositional tool to generate a musical structuring element - pitch collections, like a scale that doesn’t simply doesn’t replicate at the octave Rhythm sieves, however, are a compositional tool to generate fleshed out musical ideas - rhythmic motive - even if simple or not fully developed.

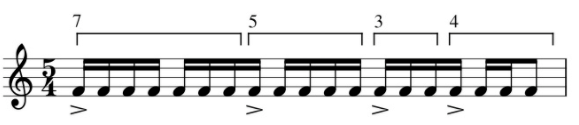

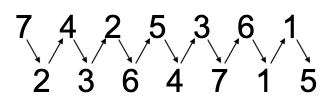

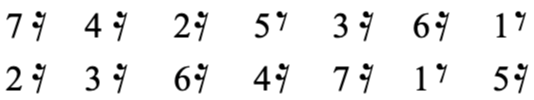

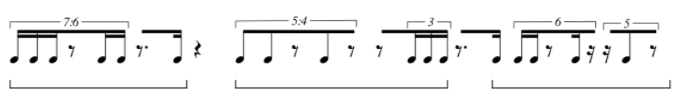

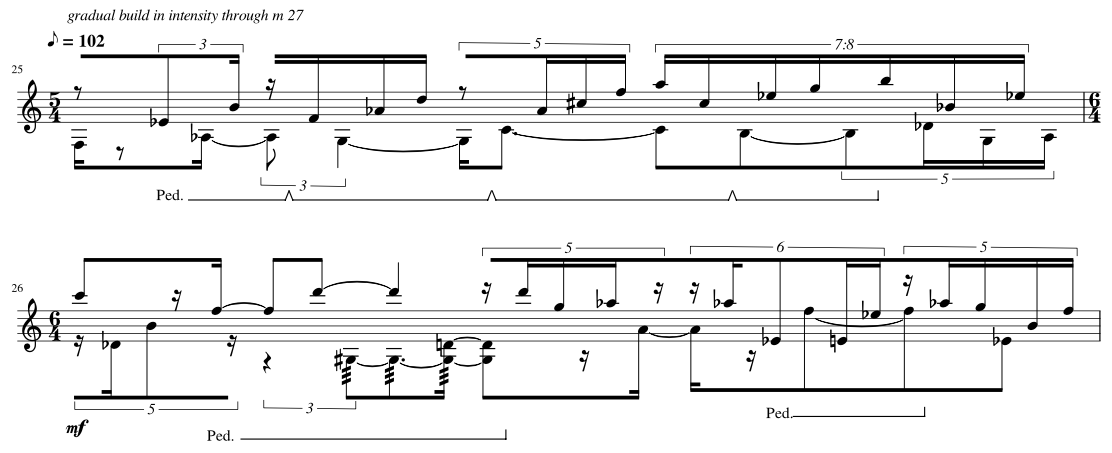

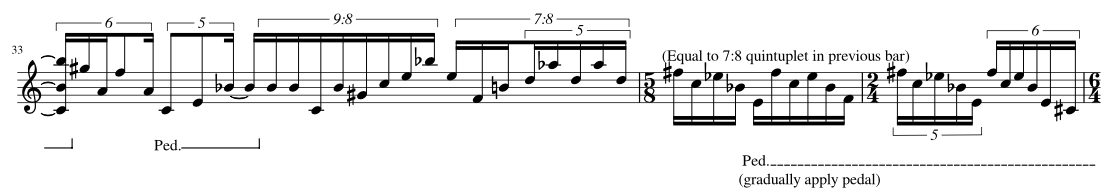

How Are They Created Again, the information presented below is not how sieves are generated or used in Xenakis’ music, but rather a collection of proportional filtering and mapping techniques I’ve developed and used over the last decade, primarily in the last 5 years. Conceptually they produce the same results as Xenakis, but through different means. The following are the procedures that I’ve defined 1. Proportion sequence (example 7:5:3:4) mapped directly onto beat structure 2. Proportion sequence mapped with beat/temporal variation among each element and beat 3. Interlaced number sequences representing impulses and rest a. Interlaced mapped with fixed beat duration b. Interlaced with variable beat duration 4. Overlaid number sequences representing impulses and rest Impulse refers to an audible note of undefined duration, and is the term that will be used moving forward. Proportion Sequence - set of values that have no fixed musical meaning, but are simply values. We’ll use 7:5:3:4 and will map that in various ways. Sequence Mapped Directly Onto Beat Structure, No Variation (step by step instructions) Let’s start with the proportion sequence mentioned above - 7:5:3:4. There are two ways to look at this, the first is that a total range is divided into collections of equal subdivisions, such as the example below: Example 1 This is a fairly basic approach to this filtering process, as it really just consists of stringing together a sequence of numeric values mapped onto a sequence of beat subdivisions. That said, there are a number of ways this could be applied compositionally, as layered streams of repetitive note sequences but misaligned accent patterns. Notice that if you were to repeat the sequence it would begin on the 4th sixteenth note of the fifth beat. This would create a similar effect as we saw in pitch sieves wherein the pattern of half-steps repeats at less than an octave, causing inconsistent pitch collections between octaves. That same approach applied to rhythm results in an accent pattern that does not necessarily repeat on strong downbeats or aligned with overarching metric structure. This sequence could also be broken by rests to create variation to the pattern: Example 2 Another approach for mapping the proportion sequence directly onto a beat structure is to simply divide each beat into the specified division. Example 3 Each beat is divided by the rhythmic value denoted by the element of the sequence - septuplet, quintuplet, triplet, quadruplet. I wouldn’t necessarily consider this a completed sieve, though. This is an example of what I would use for creating an internal shift of energy within a measure of collection of beats - the sequence could also be mapped over a longer period of time - but ultimately this particular example is a building block for a more fleshed out motive. I consider this to be a fairly basic approach to rhythm sieves, but it is a helpful way to break away from standard duple or triple beat divisions. The second basic method of mapping a proportional sequence is to define a fixed amount of musical time (e.g. a whole note) and then have each element of the sequence take up unequal slices of musical time. This creates internal variation, rendering the actual proportions meaningless, but the result maintains the same division of individual accented impulses. An example of this is shown below using the same 7:5:3:4 collection but the collections of impulses take up different durations of musical time. Sequence Mapped Directly Onto Beat Structure, Variation Across Beats The example below uses the same number sequence, but notice the 7 takes up two beats, the 5 takes up a single beat, and 3 and 4 each take up half a beat. Example 4 Here’s an example of how you can use the same number of audible notes, but the rhythmic values themselves change and cross beats. Example 5 Notice how each new element in the sequence comes just after each downbeat, similar to Example 2. The beat divisions change on each beat of the measure, similar to Example 3, but the rate of the final element 4 takes up less than a full beat similar to Example 4. This particular example is a combination of all the basic approaches to mapping a proportion sequence (in some cases just a simple integer sequence) onto a collection of beats or range of musical time. The basic mapping procedures above are conceptually similar to pitch sieves, in that a given range is divided in some way, leaving only portions of the whole. The next collection of methods are more complex and generate more variation than what the basic processes can typically produce. A main difference between the complex sieves and the simple sieves is that complex sieves don’t require a fixed range (or even a defined range at all). They can simply be interlaced or concatenated sequences that go on ad infinitum. Interlaced Number Sequences for Notes and Rests The complex sieves take rests into account, not just simple subdivisions of beats. In order to create musical motives we have to take silence and durational variation into account. My approach to this type of sieve is to create two sequences of numbers - these can have repeated values or can be a unique random numbers. One sequence corresponds to audible sound, the impulses. The first example will combine elements of basic beat mapping, wherein each element of both sequences is a fixed duration, in this case a 16th note. Two sequences are listed below Impulse Sequence (7, 4, 2, 5, 3, 6,1) Rest Sequence (2, 3, 6, 4, 7, 1,5) The first procedure will be interlacing the two sequences starting with the impulse sequence, which creates the following: Example 6 And when written out as a rhythmic sequence: Example 7 Each bracketed collection of impulses corresponds to its ordered element in the sequence - the same goes for the rests - but this doesn’t have to be the end of the sequence. Just because the result is shown as a sequence of 16th notes doesn’t mean all rhythmic values have to be the same. This is where creative compositional choices come into play, which we’ll look at further in this article. From this point you can start to create variation within the sequence by assigning a specific rhythmic value to each element. Here’s an example of what that might look like: Example 8 In this case the values are defined differently. For the impulses, the rhythmic value represents the fixed duration and the number represents the total number of impulses to be used during that time. The first element would be 7 impulses over the duration of a dotted quarter. Some kind of tuplet would have to be used even if the 7 impulses aren’t the same duration, but the rest that follows has to fit within the preceding tuplet structure. The durations for the rests represent the actual number of that duration. So the first element in the rest sequence refers to two 8th rests. These don’t have to be duple divisions of a strict quarter note, but could instead take up 2 eighths contained in a tuplet. Here is an example of this interlaced sequence with durational variation Example 9 At this point the results from these procedures are more musical in nature. Notice in Example 9 many of the impulse groups aren’t all a single duration. This is how you can build additional variation into your sequences. You can take this a step further by adding ties. While that technically alters the number of impulses you still have chunks of durations that fit within the scheme established by the sequence. Overlaid Number Sequences for Notes and Rests The final approach to using impulse and rest sequences is to overlay one sequence onto the other. This is similar to the pitch sieve structure where two interval series are applied to a single range.This last approach is harder to deconstruct from the final product, so I’ll break it down step by step. We’ll use the same number sequences as before. This time rather than have the elements follow one another, each will form a pair consisting of x number of impulses and y number of rests. Given Example 9 above those combined sequences would look like this: Example 10 In this final method we’ll take these one at a time. In the first pair we have 7 sixteenth impulses and 2 sixteenth rests. My approach here is to place the rests within the collection of impulses. In the event I have more rests than impulses (see element 3 with (2,6)) I typically remove the impulse entirely for a longer rest. There are other rules you could apply, such as defaulting to the larger value and fitting the smaller value inside of it. The example below shows the overlaid sequence above wherein I remove impulses if the rest value is larger Example 11 Notice the bracketed groupings. They follow a similar energy trajectory and grouping in that they all consist of three events punctuated by rest. Furthermore, the first two contain a block of 1, 2 and 3 impulses, the last containing a grouping of 3 and two instances of 1, but you could take artistic license here and add a second impulse to the last bracketed collection. That would also give you three short phrases of impulses 3-2-1, 2-1-3, and 3-1-2. These could be used as a single extended phrase structure or can be fragmented. Again, these sieves can create complete rhythmic sequences or can be used to generate lots of scraps of rhythmic material to be assembled some other way. Uses of Rhythm Sieves In short, I’ve found three primary uses I’ve found in using them in my own music 1. Proportional relationships (same sequence mapped over different durations) 2. Modern take on isorhythm 3. Cohesion without repetition This section should be regarded as a “how does Jon use rhythm sieves” because the process outlined above has so many possibilities, even when the end result is a fully composed rhythmic motive. As mentioned above, they can be used to generate small rhythmic ideas that can be strung together in various ways, or you could generate a longer rhythm sequence and use it as is. You could resort to thr time-tested techniques for layering rhythms through imitative or invertible counterpoint, even simple rotations or retrogrades can give you a wealth of material to draw from. In 2019 I wrote two pieces with extensive use of the rhythm sieve procedures outlined above. The first was Mercurial Tendencies II: Marbled Cobalt for solo vibraphone, and the other is Struggling to Breathe for two Disklaviers. In Marbled Cobalt I used simpler sieve procedures to create short rhythm cells, then ordered them in various ways to create a constant push and pull in terms of energy, and used rhythm as a primary source of tension and release. A common theme in the piece is overlaid rhythms that develop over time to become more or less complex depending on the context of the music that comes before and after. This was my first time using sieves as the exclusive method for generating rhythm. It was very illuminating and presented a challenge I hadn’t come up against in previous works. While I’ve always loved integral serialism of the mid-20th century, I found its approach to serializing rhythm incredibly counter-intuitive. Using sieves allowed me to work within constraints of a system I designed to generate my material, but I wasn’t beholden to the results. Because the sieve procedures are inherently a filtering/mapping process (Xenakis/Ferneyhough) rather than generative (Boulez/Stockhausen/Berio), I feel like I have more control over my material in how it’s applied in mico- and macro-structures of the composition. Below are two score excerpts from Mercurial Tendencies II: Marbled Cobalt (performed by Tony Donofrio) Example 12a (click image for audio) This is an example of two contrapuntal lines. The top line was created using an impulse and rest sequence. The lower line was originally created with an impulse sequence and the rests were added later to fit “inside” the top line. When the two are layered together you can hear the interplay and internal instability that can change quickly (the “mercurial”) Example 12b (mm. 33-35) This is an example of the simple procedure of assigning a number of impulses to a beat or collection of subdivisions. Notice that each beat (sometimes two beats or fractions of beats) are divided into a different number of subdivisions. Beats 1-34of m. 33 shows an increase of energy on each beat, but to varying degrees. But beats 5-6 divide 8 sixteenths into 7 - a slowing of energy - while dividing the last 4 impulses into a quintuplet, simultaneously speeding up and slowing down. In Struggling to Breath I used sieves because of how easy it is to manipulate proportions, and because I knew that Disklaviers would be able to replicate nearly any rhythm I could generate. Over a year had passed since I wrote Marbled Cobalt, and I wanted to approach the sieves with more intention. The central concept/narrative of Struggling to Breathe was inspired by a very nasty lung infection I had in September 2019. The two Disklaviers play almost together throughout the piece, or at least are presenting similar moods and energies. The sieves made it easier to create both short and long rhythmic motives that could be ordered like patchwork between the two instruments. Below are examples of Struggling to Breathe. You can listen to this piece on my album Galvanized, available on all streaming services. Example 13a This is a moment that appears 5 times in the piece, the first instance notated above, the final 2 at a slower tempo and over a longer portion of musical time. It’s a perfect example of using a single rhythm sieve as a means of motivic alteration and development through simple proportional changes. Disclaimer: I'm aware that 4:3 inside 3:2 in a bar of 2|8 is just 4 16th notes. It's an intentional "mistake" along with a handful of other "mistakes" related to the central concept of the piece. Since it's written for 2 Disklaviers, the "mistakes" are more of a tongue-in-cheek joke rather than serious notation. Example 13b This is the final appearance of the motive. Notice the measure of inserted rest (artistic license) and the 6|4 bar that shows different proportions of the same idea. Measure 96 presents the same material without being under the top-level tuplet (3:2 in all) in all 4 voices, effectively slowing the energy and making the layered impulse groupings clearer to identify. There are some liberties taken, but again, artistic license. If you want to take a deeper look at the score for either of these pieces they can be found on my website (www.jonfielder.com) or you can just click the links below.

Mercurial Tendencies II: Marbled Cobalt (score) Struggling to Breathe (score) (Apple Music) (Spotify) Hopefully you found this helpful and gave you some ideas for how to experiment with these procedures in your own music. Remember that sieves aren’t just for creating the angular, dissonant, kerplunkity - devotees, that one is for you - music shown above; but can be used in all kinds of applications relevant to varying styles and aesthetics. Think of sieves as a compositional tool rather than a means to an aesthetic end. I assure you that the sieves will be easier to understand and the possibilities increase dramatically. Much like other mathematically oriented musical systems, using sieves takes time and practice, and I’ve found the best way to get good results is to dive in and try it. Start small with simple procedures - take fragments and try putting them together by entering rests as you like. Try layering the cells to create a more minimalist driving rhythm. Create short phrases and then make a dozen variations of that phrase using the same basic sieve structure. See if you can create a single sieve (a simpler one is better) that generates a full rhythm motive, then see if you can use that phrase in different stylistic contexts. There are countless applications not bound by style or aesthetic. The only limitations are the ones you, as the composer, place on the system and the artistic implementation of the results.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The "Direct Sound" Page is dedicated to general blog posts and discussions. Various topics are covered here.

Full Directory of Articles |