|

This is a long overdue article that I’ve been getting email requests for since 2015, and it seems like a good time to finally write it. For those of you who have been waiting with bated breath, I hope it lives up to your expectations. As for everyone else, I hope you find this informative and engaging, and as always my inbox is always open for questions. Enjoy! Sieves: What are they Sieves are rhythmic cells and/or longer rhythmic sequences created through basic filtering, mapping, and overlay procedures. They can be simple or quite complex depending on what your goals and working methods are. The concept of sieves is associated primarily with Greek composer/mathematician/architect/awesome dude Iannis Xenakis. My article here is not going to cover the specific processes that Xenakis used because, full disclosure, it’s more complicated math than my brain is able to explain in a simple way (let alone fully understand…), and I’ve found my own idiosyncratic ways to perform similar processes and get quality results. That said, if you’re interested in learning about Xenakis’ rhythmic sieves you can check out Xenakis’ own book Formalized Music (Pendragon Press, 1963…good luck finding this one), James Harley’s Xenakis: His Life In Music (Routledge, 2004) or for the Max/MSP-minded there’s this very nice video. Rhythm sieves are similar in concept to pitch sieves but different application in order to account for multiple degrees of variation

Another primary difference is that pitch sieves are a compositional tool to generate a musical structuring element - pitch collections, like a scale that doesn’t simply doesn’t replicate at the octave Rhythm sieves, however, are a compositional tool to generate fleshed out musical ideas - rhythmic motive - even if simple or not fully developed.

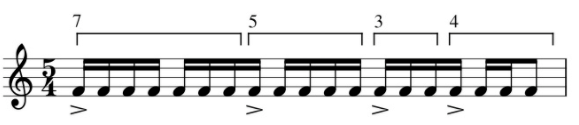

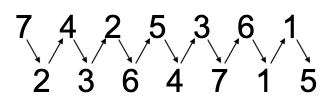

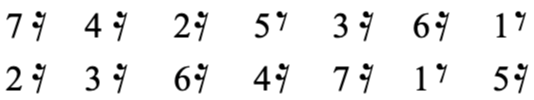

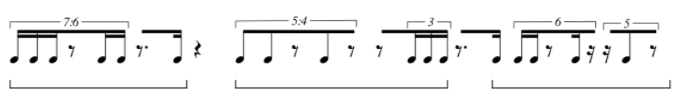

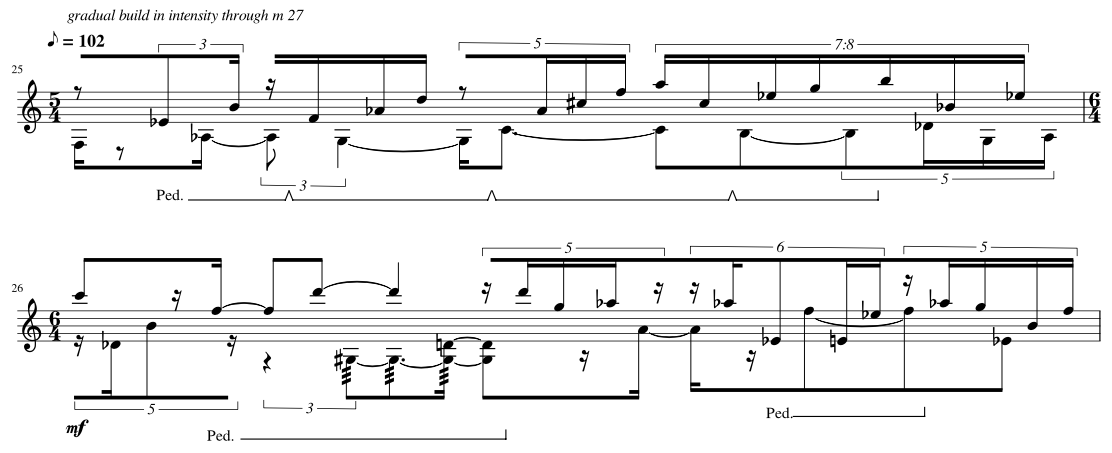

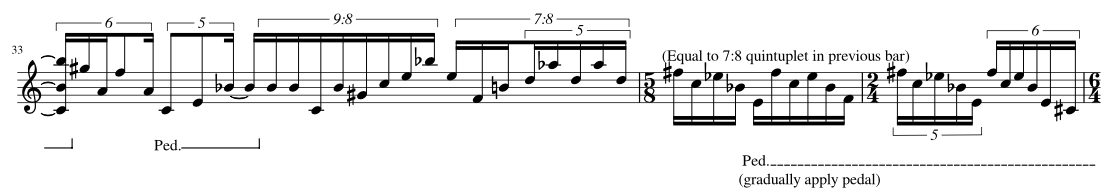

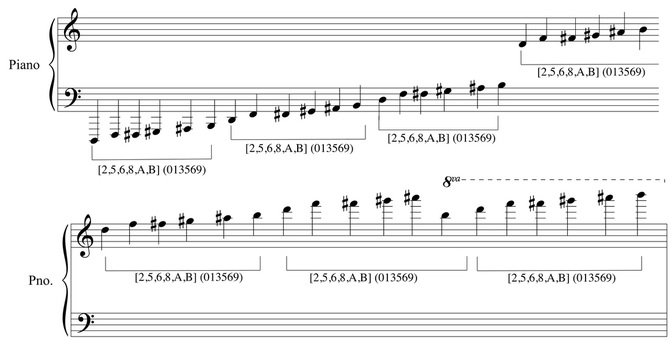

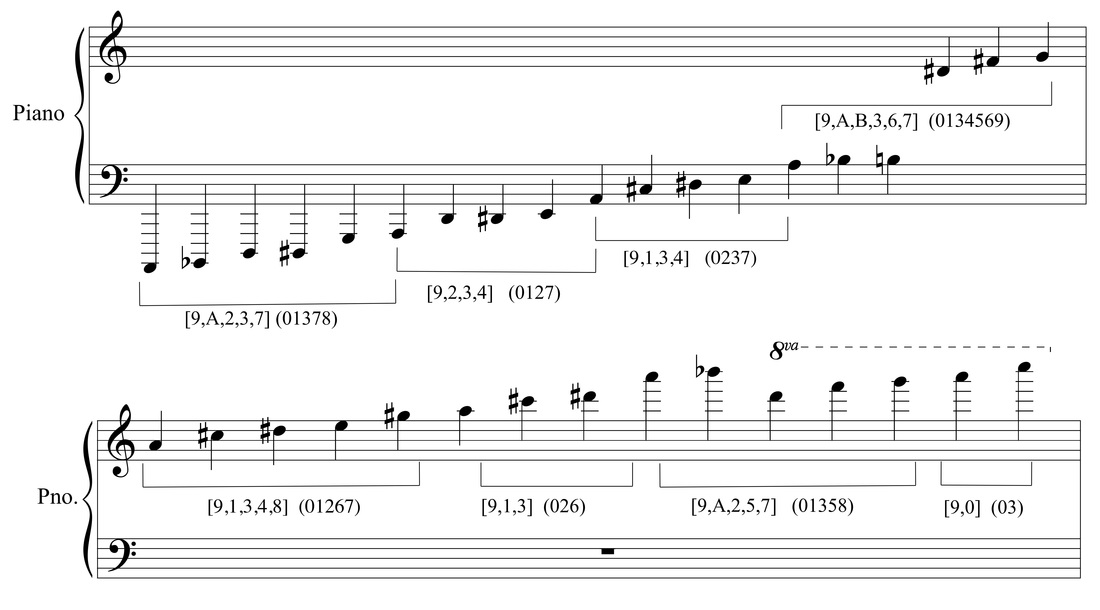

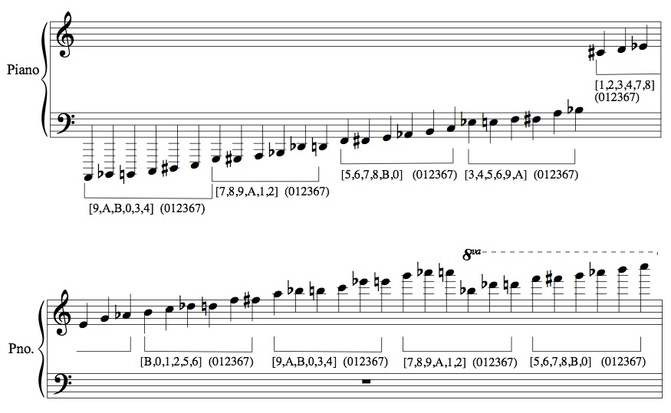

How Are They Created Again, the information presented below is not how sieves are generated or used in Xenakis’ music, but rather a collection of proportional filtering and mapping techniques I’ve developed and used over the last decade, primarily in the last 5 years. Conceptually they produce the same results as Xenakis, but through different means. The following are the procedures that I’ve defined 1. Proportion sequence (example 7:5:3:4) mapped directly onto beat structure 2. Proportion sequence mapped with beat/temporal variation among each element and beat 3. Interlaced number sequences representing impulses and rest a. Interlaced mapped with fixed beat duration b. Interlaced with variable beat duration 4. Overlaid number sequences representing impulses and rest Impulse refers to an audible note of undefined duration, and is the term that will be used moving forward. Proportion Sequence - set of values that have no fixed musical meaning, but are simply values. We’ll use 7:5:3:4 and will map that in various ways. Sequence Mapped Directly Onto Beat Structure, No Variation (step by step instructions) Let’s start with the proportion sequence mentioned above - 7:5:3:4. There are two ways to look at this, the first is that a total range is divided into collections of equal subdivisions, such as the example below: Example 1 This is a fairly basic approach to this filtering process, as it really just consists of stringing together a sequence of numeric values mapped onto a sequence of beat subdivisions. That said, there are a number of ways this could be applied compositionally, as layered streams of repetitive note sequences but misaligned accent patterns. Notice that if you were to repeat the sequence it would begin on the 4th sixteenth note of the fifth beat. This would create a similar effect as we saw in pitch sieves wherein the pattern of half-steps repeats at less than an octave, causing inconsistent pitch collections between octaves. That same approach applied to rhythm results in an accent pattern that does not necessarily repeat on strong downbeats or aligned with overarching metric structure. This sequence could also be broken by rests to create variation to the pattern: Example 2 Another approach for mapping the proportion sequence directly onto a beat structure is to simply divide each beat into the specified division. Example 3 Each beat is divided by the rhythmic value denoted by the element of the sequence - septuplet, quintuplet, triplet, quadruplet. I wouldn’t necessarily consider this a completed sieve, though. This is an example of what I would use for creating an internal shift of energy within a measure of collection of beats - the sequence could also be mapped over a longer period of time - but ultimately this particular example is a building block for a more fleshed out motive. I consider this to be a fairly basic approach to rhythm sieves, but it is a helpful way to break away from standard duple or triple beat divisions. The second basic method of mapping a proportional sequence is to define a fixed amount of musical time (e.g. a whole note) and then have each element of the sequence take up unequal slices of musical time. This creates internal variation, rendering the actual proportions meaningless, but the result maintains the same division of individual accented impulses. An example of this is shown below using the same 7:5:3:4 collection but the collections of impulses take up different durations of musical time. Sequence Mapped Directly Onto Beat Structure, Variation Across Beats The example below uses the same number sequence, but notice the 7 takes up two beats, the 5 takes up a single beat, and 3 and 4 each take up half a beat. Example 4 Here’s an example of how you can use the same number of audible notes, but the rhythmic values themselves change and cross beats. Example 5 Notice how each new element in the sequence comes just after each downbeat, similar to Example 2. The beat divisions change on each beat of the measure, similar to Example 3, but the rate of the final element 4 takes up less than a full beat similar to Example 4. This particular example is a combination of all the basic approaches to mapping a proportion sequence (in some cases just a simple integer sequence) onto a collection of beats or range of musical time. The basic mapping procedures above are conceptually similar to pitch sieves, in that a given range is divided in some way, leaving only portions of the whole. The next collection of methods are more complex and generate more variation than what the basic processes can typically produce. A main difference between the complex sieves and the simple sieves is that complex sieves don’t require a fixed range (or even a defined range at all). They can simply be interlaced or concatenated sequences that go on ad infinitum. Interlaced Number Sequences for Notes and Rests The complex sieves take rests into account, not just simple subdivisions of beats. In order to create musical motives we have to take silence and durational variation into account. My approach to this type of sieve is to create two sequences of numbers - these can have repeated values or can be a unique random numbers. One sequence corresponds to audible sound, the impulses. The first example will combine elements of basic beat mapping, wherein each element of both sequences is a fixed duration, in this case a 16th note. Two sequences are listed below Impulse Sequence (7, 4, 2, 5, 3, 6,1) Rest Sequence (2, 3, 6, 4, 7, 1,5) The first procedure will be interlacing the two sequences starting with the impulse sequence, which creates the following: Example 6 And when written out as a rhythmic sequence: Example 7 Each bracketed collection of impulses corresponds to its ordered element in the sequence - the same goes for the rests - but this doesn’t have to be the end of the sequence. Just because the result is shown as a sequence of 16th notes doesn’t mean all rhythmic values have to be the same. This is where creative compositional choices come into play, which we’ll look at further in this article. From this point you can start to create variation within the sequence by assigning a specific rhythmic value to each element. Here’s an example of what that might look like: Example 8 In this case the values are defined differently. For the impulses, the rhythmic value represents the fixed duration and the number represents the total number of impulses to be used during that time. The first element would be 7 impulses over the duration of a dotted quarter. Some kind of tuplet would have to be used even if the 7 impulses aren’t the same duration, but the rest that follows has to fit within the preceding tuplet structure. The durations for the rests represent the actual number of that duration. So the first element in the rest sequence refers to two 8th rests. These don’t have to be duple divisions of a strict quarter note, but could instead take up 2 eighths contained in a tuplet. Here is an example of this interlaced sequence with durational variation Example 9 At this point the results from these procedures are more musical in nature. Notice in Example 9 many of the impulse groups aren’t all a single duration. This is how you can build additional variation into your sequences. You can take this a step further by adding ties. While that technically alters the number of impulses you still have chunks of durations that fit within the scheme established by the sequence. Overlaid Number Sequences for Notes and Rests The final approach to using impulse and rest sequences is to overlay one sequence onto the other. This is similar to the pitch sieve structure where two interval series are applied to a single range.This last approach is harder to deconstruct from the final product, so I’ll break it down step by step. We’ll use the same number sequences as before. This time rather than have the elements follow one another, each will form a pair consisting of x number of impulses and y number of rests. Given Example 9 above those combined sequences would look like this: Example 10 In this final method we’ll take these one at a time. In the first pair we have 7 sixteenth impulses and 2 sixteenth rests. My approach here is to place the rests within the collection of impulses. In the event I have more rests than impulses (see element 3 with (2,6)) I typically remove the impulse entirely for a longer rest. There are other rules you could apply, such as defaulting to the larger value and fitting the smaller value inside of it. The example below shows the overlaid sequence above wherein I remove impulses if the rest value is larger Example 11 Notice the bracketed groupings. They follow a similar energy trajectory and grouping in that they all consist of three events punctuated by rest. Furthermore, the first two contain a block of 1, 2 and 3 impulses, the last containing a grouping of 3 and two instances of 1, but you could take artistic license here and add a second impulse to the last bracketed collection. That would also give you three short phrases of impulses 3-2-1, 2-1-3, and 3-1-2. These could be used as a single extended phrase structure or can be fragmented. Again, these sieves can create complete rhythmic sequences or can be used to generate lots of scraps of rhythmic material to be assembled some other way. Uses of Rhythm Sieves In short, I’ve found three primary uses I’ve found in using them in my own music 1. Proportional relationships (same sequence mapped over different durations) 2. Modern take on isorhythm 3. Cohesion without repetition This section should be regarded as a “how does Jon use rhythm sieves” because the process outlined above has so many possibilities, even when the end result is a fully composed rhythmic motive. As mentioned above, they can be used to generate small rhythmic ideas that can be strung together in various ways, or you could generate a longer rhythm sequence and use it as is. You could resort to thr time-tested techniques for layering rhythms through imitative or invertible counterpoint, even simple rotations or retrogrades can give you a wealth of material to draw from. In 2019 I wrote two pieces with extensive use of the rhythm sieve procedures outlined above. The first was Mercurial Tendencies II: Marbled Cobalt for solo vibraphone, and the other is Struggling to Breathe for two Disklaviers. In Marbled Cobalt I used simpler sieve procedures to create short rhythm cells, then ordered them in various ways to create a constant push and pull in terms of energy, and used rhythm as a primary source of tension and release. A common theme in the piece is overlaid rhythms that develop over time to become more or less complex depending on the context of the music that comes before and after. This was my first time using sieves as the exclusive method for generating rhythm. It was very illuminating and presented a challenge I hadn’t come up against in previous works. While I’ve always loved integral serialism of the mid-20th century, I found its approach to serializing rhythm incredibly counter-intuitive. Using sieves allowed me to work within constraints of a system I designed to generate my material, but I wasn’t beholden to the results. Because the sieve procedures are inherently a filtering/mapping process (Xenakis/Ferneyhough) rather than generative (Boulez/Stockhausen/Berio), I feel like I have more control over my material in how it’s applied in mico- and macro-structures of the composition. Below are two score excerpts from Mercurial Tendencies II: Marbled Cobalt (performed by Tony Donofrio) Example 12a (click image for audio) This is an example of two contrapuntal lines. The top line was created using an impulse and rest sequence. The lower line was originally created with an impulse sequence and the rests were added later to fit “inside” the top line. When the two are layered together you can hear the interplay and internal instability that can change quickly (the “mercurial”) Example 12b (mm. 33-35) This is an example of the simple procedure of assigning a number of impulses to a beat or collection of subdivisions. Notice that each beat (sometimes two beats or fractions of beats) are divided into a different number of subdivisions. Beats 1-34of m. 33 shows an increase of energy on each beat, but to varying degrees. But beats 5-6 divide 8 sixteenths into 7 - a slowing of energy - while dividing the last 4 impulses into a quintuplet, simultaneously speeding up and slowing down. In Struggling to Breath I used sieves because of how easy it is to manipulate proportions, and because I knew that Disklaviers would be able to replicate nearly any rhythm I could generate. Over a year had passed since I wrote Marbled Cobalt, and I wanted to approach the sieves with more intention. The central concept/narrative of Struggling to Breathe was inspired by a very nasty lung infection I had in September 2019. The two Disklaviers play almost together throughout the piece, or at least are presenting similar moods and energies. The sieves made it easier to create both short and long rhythmic motives that could be ordered like patchwork between the two instruments. Below are examples of Struggling to Breathe. You can listen to this piece on my album Galvanized, available on all streaming services. Example 13a This is a moment that appears 5 times in the piece, the first instance notated above, the final 2 at a slower tempo and over a longer portion of musical time. It’s a perfect example of using a single rhythm sieve as a means of motivic alteration and development through simple proportional changes. Disclaimer: I'm aware that 4:3 inside 3:2 in a bar of 2|8 is just 4 16th notes. It's an intentional "mistake" along with a handful of other "mistakes" related to the central concept of the piece. Since it's written for 2 Disklaviers, the "mistakes" are more of a tongue-in-cheek joke rather than serious notation. Example 13b This is the final appearance of the motive. Notice the measure of inserted rest (artistic license) and the 6|4 bar that shows different proportions of the same idea. Measure 96 presents the same material without being under the top-level tuplet (3:2 in all) in all 4 voices, effectively slowing the energy and making the layered impulse groupings clearer to identify. There are some liberties taken, but again, artistic license. If you want to take a deeper look at the score for either of these pieces they can be found on my website (www.jonfielder.com) or you can just click the links below.

Mercurial Tendencies II: Marbled Cobalt (score) Struggling to Breathe (score) (Apple Music) (Spotify) Hopefully you found this helpful and gave you some ideas for how to experiment with these procedures in your own music. Remember that sieves aren’t just for creating the angular, dissonant, kerplunkity - devotees, that one is for you - music shown above; but can be used in all kinds of applications relevant to varying styles and aesthetics. Think of sieves as a compositional tool rather than a means to an aesthetic end. I assure you that the sieves will be easier to understand and the possibilities increase dramatically. Much like other mathematically oriented musical systems, using sieves takes time and practice, and I’ve found the best way to get good results is to dive in and try it. Start small with simple procedures - take fragments and try putting them together by entering rests as you like. Try layering the cells to create a more minimalist driving rhythm. Create short phrases and then make a dozen variations of that phrase using the same basic sieve structure. See if you can create a single sieve (a simpler one is better) that generates a full rhythm motive, then see if you can use that phrase in different stylistic contexts. There are countless applications not bound by style or aesthetic. The only limitations are the ones you, as the composer, place on the system and the artistic implementation of the results.

0 Comments

Article by guest contributor Andrew Selle Anyone who even remotely engages with popular culture will be extremely familiar with the trope I am about to describe. You’re watching some mindless television show or move, and a scene takes place in some yuppie-intellectual location that boomers love to hate: a coffee shop, a bookstore, anything with the word “artisanal” in it, etc. The person at the counter looks like they are absolutely hating their very existence, and we come to learn that they went to college for something “useless” like art history, gender studies, or the like. We cut to the sharp, capital-minded main character, and they say something like “Well, that kind of explains it, huh?” Cue laugh track, rinse, repeat. In a very clear way, this cultural trope labels this person working a low-earning job as failed not just because they do not earn much money or have an “exciting” career, but also because they were stupid enough to go to college and study something that so clearly wasn’t going to provide for their financial future. While we might say that this is just a simple instance of poking fun and that we should have thicker skin (certainly this is a requirement for success in the arts), I would argue that this actually points to a larger cultural problem relating to the way we view the role of academia and the arts in society. Even more, it points to a fundamental issue with the ways in which society attributes value, namely, that it often correlates a pursuit’s value with its capacity to generate wealth or power. In a capitalist society, this should come as no surprise; however, this creates an obvious discontinuity between said society and academic/artistic pursuits: if pursuits which have a high potential for wealth creation are positively valenced from a cultural-capital standpoint, the opposite must be true of those pursuits that do not inherently create wealth. Herein lies the problem. This problem first presented itself to me a number of years ago as I was reading an editorial in the Wall Street Journal by Douglas Belkin entitled “Many Colleges Fail in Teaching how to Think.” In his article, Belkin rightly asserts that students are often spending 4+ years in college but not coming out with many more critical thinking skills than they enter with. Those of us that have been around academic for any amount of time know this all too well. Unfortunately, he is far too quick to pin this on the universities themselves (evidenced by his title saying the colleges themselves fail). What he misses is that universities have been so culturally pressured to become vocational institutions rather than institutions of higher learning, such that the critical thinking skills he is referring to have no place in the curriculum anymore. Modern culture has become so preoccupied with the university degree as a route to monetary success, and universities have responded to that pressure. After reading this, I was so incensed that I quickly began typing up a letter to the editor. While I will not recount my entire tirade here, one bit of research that I did sticks out. In his 1873 text The Role of the University, John Henry Newman addresses this issue. He says, “If then a practical end must be assigned to a University course, I say it is that of training good members of society…” Herein lies the value of a university education; it lies in broadening one’s horizons, coming into contact with people and ideas that are foreign to you, and the pursuit of learning and critical thinking for their own sake. The value in a university education is distinctly not monetary; the institution of the university itself was never designed with this in mind. Thus, we arrive at the tension between the intrinsic nature of the university (the pursuit of education) and the cultural shift in the view of the university (as vocational preparation and wealth creation). So, where does this leave the arts? I think there are two very clear ramifications for the arts that result from this sort of societal and cultural pressure. One is obvious, the other, less so. First, and most obviously, in a cultural context that positively values those pursuits that generate wealth and/or power, the arts is in a bit of a bind in that it typically is not a huge generator for either. (Yes, artists that make it really big tend to make a lot of money, but the proportion of artists that make an above average salary compared to, say, accountants or lawyers is certainly smaller.) Thus, arts programs at all levels of education have to find ways to justify their existence in the absence of a realistic potential to be lucrative. We hear these tropes all the time: “Arts make the world worth living in,” “Kids who are involved in the arts to better in school,” and most nefarious of all, “Highly creative people are highly employable people.” (These are just a few of the many.) In this way, arts programs have to define their value and their success not on intrinsic factors like personal fulfillment and creative experience, but rather as a utility to external forces such as employability and performance in other facets of modern life deemed more “useful.” There is, however, a second, less obvious issue that arises when we determine value in this manner. Not only do the arts themselves need to justify their own existence, but I have found that artists themselves split into sects and infight over whose pursuits are more marketable. I was very fortunate to attend a university for my two composition degrees that never really concerned itself with the amount of money that a student’s work might generate. Never once did I hear someone say “Well, that’s an interesting idea, but no one is going to buy it.” However, we all know that this is not the case everywhere. Every day, students’ artistic pursuits across the country are guided by speculation of future success as measured by marketability and not creativity. Of course, I can certainly forgive an institution for pushing their students toward more marketable forms of artistic expression when the institution’s very livelihood (and that of the department) rests on their students becoming successful in terms of the culture that surrounds it. It is all too easy to point the finger at the institutions, but the finger should really be pointed at contemporary culture, and ultimately, ourselves. That, out of all of this, might be the toughest pill to swallow. We all, in some way or another, are complicit in this modern system of “university as vocational training.” This is where the crux of the issue lies: with us. I am guilty of this, without question. For years, I justified my pursuits of experimental and contemporary music by saying things like, “Well, you’d be surprised how much money you can actually make doing it,” or, “I know it’s not the most lucrative career field itself, but I’m definitely learning skills that could get me into something a little bit more secure,” etc. I’m sure you’ve all said something similar; as ashamed as I am, culture is one hell of a drug. However, here is my plea: no more. No more should we have to justify our pursuits by anything other than their intrinsic value. Toward the end of my doctorate, I was often getting the question, “Huh, so music theory…what are you going to do with that?” It took me a while, but I finally started answering, “What do you mean? I’m doing it now.” Those were some of the most empowering words I ever said, and still feel so to this day. To those of you in academia, the arts, culture studies, or any sort of related field that contemporary culture hasn’t sanctified as “valuable,” I would encourage you to define your success in the self-fulfillment of the pursuit itself. Do not feel pressured to justify your actions in terms of some future or tangential monetary or cultural gain. At the heart of it all, there is honor and value in the pursuit of learning and creative expression of any kind. If you wake up and get excited about the art you make, the words you write, the things you read and study, and the thoughts and feelings that these pursuits stir within you, you are successful. Ultimately, it is up to the university itself (and those of us involved in academia) to try to reorient the cultural milieu around the institution. We should advocate for these pursuits not because our students will earn high-paying jobs (though they might) or because they will be ensconced into positions of power and import, but because these pursuits are an inherent part of being a good citizen. To return to Mr. Belkin’s editorial, we need to remove the vocational aspect of the university and teach our students and each other to be critically-minded individuals. That, and not the potential to amass wealth, should be the cultural marker of success. In other words, is it the art-historian barista who has found intellectual fulfillment that is the failure, or is it the expression-starved culture that needs to be reassured that they are fulfilled?  Dr. Andrew Selle is a music theorist and composer and is currently a lecturer in music theory at Purdue University Fort Wayne. In true Nietzshean fashion I am here to proclaim The Audience Is Dead...or at the very least it does not exist. Obviously this is a bit dramatic, but not entirely untrue. I decided to write this post after reading a recent article run by RTE (Ireland’s National Television and Broadcast media outlet) titled “Is Experimental Music Killing Classical Music?” by Dave Flynn. The following is not specifically in reference to Flynn’s article (which for the record I find to be unbelievable off-base), but more in response to the many discussions that ensued in online forums and across social media. A conversation I often found myself in with other composers, performers, theorists, musicologists and even casual listeners of contemporary music focused on whether or not Flynn is right in reference to writing music “for the audience,” and the general “accessibility” of said music. I have always found both of those sentiments frustrating for a number of reasons, all of which I will discuss (and vent about) below.

Before getting into any kind of nuanced discussion of why the concept of writing for “the audience” is problematic I would like to revisit my opening statement - the audience does not exist. This might seem a grandiose and even polemical statement of Boulezian proportions (not that there’s anything wrong with that), but there is a great deal of truth to it. The problem is not the idea of audience, but with the definite article used to describe the noun. It would be easy to refer to “an” audience of listeners, but “the” carries an implication of a definable audience. On the one hand this could be ignored as a nit-picky prescriptivist complaint, but I don’t see it that way. Differentiating between definite and indefinite articles is a key element here because “an” audience could denote any group of people encompassing a wide range of ideas, cultures, aesthetics, approaches, and values. However, “the” audience implies a single monolithic group of shared ideas, cultures, aesthetics, values, and, above all, shared expectations. To me it goes without saying (even though I already said it) that in order to different levels of specificity in any capacity one can easily do that through the use of definite and indefinite articles. I could say the sentence “please go get me a soda” implying that any hypothetical soda will adequately quench my thirst. However, if I were to say “please go get me the soda” that then implies I’m asking for a specific type of soda. Again, this is all straight-forward. However, this concept is often not applied when discussing art and music, specifically when discussing contemporary concert music. I find that lack of distinction quite disconcerting, though, because of the implications and restrictions it places on artists, as well as listeners. My soda example might not be the best analog to the situation of discerning between audiences, mainly because with the soda the idea is that a single person is drawing from a wide range of possible choices or from a single specified choice. When composers and performers write and program music they are creating a single entity (the piece of the concert program) that is meant to satisfy, entertain or engage a wide collection of people with varying ideas and sensibilities; the input/output is reversed so the paradigm must shift. There is quite literally no way to refer to any listening body as “the” audience in relation to aesthetic tastes and sensibilities. If you were to say “the audience will leave immediately following the last piece” well then that definite article is entirely necessary. However, the phrase “I wrote this piece with the audience in consideration” is immediately rendered meaningless because there is no way to define what “the audience” is, or who it encompasses. There is no single group of listeners/appreciators that all artists can or even should strive to please. The audience for one avenue of art could be the polar opposite of the audience that is attracted to a different type of art. To try to please both is an exercise in futility. An audience of listeners who responds positively to Post-Minimalism could potentially (and likely) have the opposite reaction to New Complexity. Does that mean that a Post-Minimalist is writing for the audience and the New Complexity composer is not? That would be a hard no. Each is writing for their own audience of listeners with a general set of expectations in mind. This leads me to my next point, which is how and why the concept of “the audience” is damaging to composers, performers, and even to any listener of any type of music. This goes back to my point above that the concept of “the” audience is a reductive concept that lumps all listeners and appreciators of art into a single category wherein its members have shared interests and expectations. How could any composer write music to please such an audience? How could a performer craft a program to engage the entire audience? Above all, as an audience member I would be a bit offended (for a fleeting moment) if a composer with diametrically opposed aesthetics told me that they were writing music for “the” audience, because they are clearly not taking my interests and tastes into account. On the same token, as a member of “the” hypothetical audience of shared interests, that audience is not taking into account the vast number of voices and styles that are available. There are a myriad of reasons that listeners might latch onto this viewpoint, specifically in the interest of maintaining what certain members might deem universal interests. However, those interests are destined in any situation to remain murky and undefined. The artist cannot expect to please everyone. The audience cannot expect to establish a single set of expectations to which the creator and curator must adhere. Furthermore, writing to the tastes of “the” audience also implies that there is a limited amount of musical material, complexity, variation and experimentation that listeners are willing to and/or capable of digesting. This simply isn’t true. As a composer of what some might deem “challenging” music, I have found that my highest compliments have come from non-musicians and from audience members who did not know what to expect from my music. In fact, in some cases where my music was an aesthetic outlier on a program, it was the lack of adhering to expectations that drew listeners in and gave them some level of pleasure in hearing my work. Does this mean you as a composer, performer or concert curator should have no consideration of who is listening to the music and what a specific group of listeners with shared interests will like? Absolutely not. All genres and styles of music have an audience to some degree, and those audiences generally want to hear what they like, not what a hypothetical body of tastemakers has approved. It’s important to know which musical elements and components make up a certain style that appeals to any given audience, but it is my personal belief that compositional decisions should not teeter on the opinions and sensibilities of an undefined group of listeners. For me, it is important to know who is primarily listening to my music, but I don’t always approach composing pieces in the same way, nor do I expect the same group of people to enjoy all of my music. Some pieces will appeal to one group of people while simultaneously boring or even irritating another. Above all, it is the duty of a composer and performer to create art, and it is the duty of listeners to seek out the music they enjoy. At the risk of possibly offending some readers, it is not my job to cater to your tastes. My final point in relation to this topic is that referring to any rigid idea of what “the” audience is really only establishes aesthetic battlegrounds and in-fighting among artists and creative minds. Composer A writes for “the audience” whereas Composer B does not, or at least not overtly. In some circles of New Music, Composer A might be seen as a paragon of contemporary music, bridging the gap between esoteric modern music and “the” audience who doesn’t want to stray far from the tried and true chestnuts of the canon. Composer B might be creating art that they truly believe in and which is creative, colorful, engaging and thought-provoking...if only they had considered “the” audience. But who determines which composer writes for “the audience” and what metrics are used to determine that? Obviously there is no answer to that question if you agree with any of what I have said above, because if the premise of the existence of “the audience” is untrue then why bother trying to determine the characteristics that define said audience. Additionally, Writing for the audience is a dog whistle term with a subtext that implies music for “the” audience is accessible, digestible, and worthy of praise or at the very least of multiple performances. This kind of idea has been used for decades to deride the art of experimental musicians (composers and performers) and of atonal, spectral, electroacoustic and all musics not deemed accessible enough. This was a constant point of discussion when I was in graduate and doctoral school, and would inevitably lead to some of the most heated and contentious discussions during composition seminars and among friends over drinks. So often I found myself explaining to friends and colleagues “I am writing for the audience...just not yours. You are writing for the audience too...just not mine.” It should be mentioned that this perceived accessibility is often (at least in my experience) viewed through the lens of orchestral programming which is historically ultra-conservative, further pointing to the dog whistle tactic of disparaging the experimental music that Flynn’s article claims is killing the canon, and Classical music altogether. In summation, it is my overall goal that we as a community of New Music makers abandon this preposterous idea of the existence of “the” audience. It really doesn’t even make sense from a linguistic standpoint - a definite article implies a definable noun or entity, which is impossible when considering subjective taste - and it definitely makes absolutely no sense from a creative or application standpoint. The concept of “the audience” rejects outside ideas, condemns experimentation and limits prospects for growth and change within an art form by limiting creativity to some imagined rubric of ideas, aesthetics and sound worlds. Beyond that, a perceived lack of audience consideration is used to level criticism against composers and performers, and to justify the exclusion of their music and art. It’s my hope that we can start to move away from this damaging and unattainable goal, and perhaps focus more on writing and programming music geared toward your own audience, whatever and whoever that might be, with the goal of simultaneously trying to reach listeners outside of your own. If you’re successful in doing that, please tell me how. In the meantime, create what you love, perform what you love, and those with shared interests will appreciate it. Those without will surely find something that appeals to them as well. BY JON FIELDER |

The "Direct Sound" Page is dedicated to general blog posts and discussions. Various topics are covered here.

Full Directory of Articles |