|

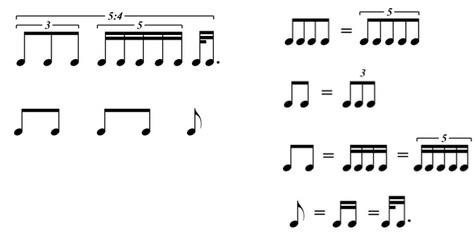

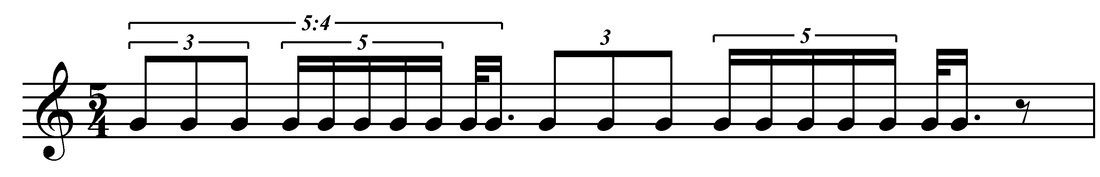

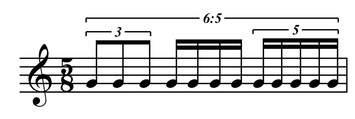

Welcome back! This is the second topic of a three-part series on rhythm techniques. The first part of the series covered the topic of irrational meter and in this part I will be discussing complex tuplets, specifically nested tuplets (tuplets inside of tuplets). This is a rhythmic device that can be perplexing and even polarizing. The very sight of a nested tuplet can send some musicians into intellectual bliss while other musicians might react with total apathy and others into a fiery rage. My goal with this post is to discuss nested tuplets, how they are created, how they can be broken down in a musical context and some reasons why a composer might choose to employ complex tuplets (whether nested or single-level) in his or her music, and ultimately the practicality (of lack thereof) of using nested tuplets. I want to begin by defining nested tuplets. A nested tuplet is a group of notes in a measure of music that have been divided into multiple levels of tuplet rhythms. In other words, the composer creates a top-level or first-level tuplet and each of the individual divisions of the tuplet can then be further divided into second-level tuplet divisions, and those into even further tuplet divisions (this can get out of hand very quickly…) to create a multi-level nested tuplet unit, which might look something like this: A nested tuplet rhythm is created using a top-down approach. First create the top-level tuplet, which looks like a typical tuplet you would see in music. When that tuplet has been created you can treat each subdivision of the tuplet individually to create a simple division of the beat (e.g. 8ths into 16ths, 16ths into 32nds, etc.) or you can divide the subdivisions into further tuplet divisions. The example above is a group of 5 eighth notes over the time of 4 eighth notes. Inside of this group of quintuple eighth notes, the first two eighths are further divided into 3 triplet eighths, the next two into a set of quintuple sixteenths and the last eighth subdivided into a 32nd note and a dotted-sixteenth (not a tuplet). This is a two-level nested tuplet in which the quintuple eighths are the top level and the triplet and quintuplet are the second level of the tuplet. Let’s break this down a little further: In this group of notes the top-level group of five 8ths are moving at a slightly faster rate than a set of four 8ths in that span of time. In turn, each of the second-level tuplets move at a faster rate than they would as top-level tuplets. The example below shows the rhythms in a single measure presented as a nested grouping and as top-level tuplet rhythms not under a grouping of 5:4 8ths. Click on the image below to hear the difference between the two. So that’s how a nested tuplet is constructed. While this might be helpful for a composer wanting to create this kind of rhythm, it isn’t very helpful for a performer who is expected to perform the rhythm. The top-down approach is, I feel, equally helpful in deconstructing these tuplets. First determine the division of the top-level tuplet, which will let you know how many equal divisions of the tuplet there are. Count out how that tuplet would sound as individual rhythmic impulses without the added tuplet and non-tuplet subdivisions. In the example above the top-level tuplet is a group of five 8ths. Start by counting two beats subdivided into 4 even 8th-notes, then two beats subdivided into five 8ths and end with a group of another group of regularly subdivided 8ths, a total of six beats. We’ll think of it as one measure of 6|4. The next step I would take would be to add the first second-level tuplet, in this case the triplet. Again, count two beats of 8ths and then the first two beats of the quintuplet 8ths would be counted as a triplet followed by the last three quintuple 8ths and finally two more beats of regularly subdivided 8ths. You could also count beat two of the measure as triplet to feel the difference between a regular triplet and the second-level nested triplet. The last step is to add the second-level tuplet, the quintuplet 16ths. Follow the same process of counting a 6|4 measure with the preceding 8ths into the nested tuplet and the final two beats of eighth notes. Add the 32nd and dotted 16th to complete the entire nested tuplet unit. The entire breakdown might look something like this: While this might seem very time-consuming, I’ve found it to be a very effective method for deconstructing how to count and feel the nested tuplets. Though I’m not a performer, I have had to follow this same process when composing nested tuplets. I think it’s important that a composer know how a nested tuplet will sound and feel in context, and this process of breaking the tuplet down piece by piece has been incredibly useful for me, both when writing my own pieces and while analysing pieces by other composers. Now that I’ve gone through defining nested tuplets, learning how to create a nested tuplet grouping and also breaking one down, the next topic at hand is the question of why a composer would choose to use this kind of rhythm. What is the benefit of nested tuplets? Well, let’s think about the purpose of using any tuplet. Tuplets of all kinds - triplets, quintuplets, etc. - are groups of notes in equal subdivisions that are not typically allowed by meter used. In more general terms, a tuplet can be used to increase or decrease the density of notes in a given amount of time and thus allowing for new rhythmic variations or a new “feel” to the music; a triplet beat that uses an 8th and a quarter note as opposed to a beat using a dotted 8th and a 16th. Nested tuplets achieve the same ends, but on multiple levels. Let’s say a composer is writing a melodic phrase consisting of 4 measure of 5|8, but with a feeling of energy gain in the final measure. The most obvious means of creating energy gain is to create a higher density of notes that move faster than what came before. One way to do this would be to simply double the rhythmic value of the notes - write 16ths instead of 8ths - but that isn’t always an elegant choice, at least not in my humble opinion. Sometimes I’m looking for a more gradual or subtle increase of energy (and yes, I have taken on the role of the hypothetical composer), so instead of doubling rhythmic values, I could choose to divide this measure of five 8ths into a set of 6 8th notes over the entire duration of the measure. Remember, though, that this is not the same as a measure of 6|8, as the six 8ths are happening over the course of what would normally be five 8ths. Now let’s also imagine that we want a gradual increase of energy within the measure from start to finish. We could then divide the first two 8ths into a triplet, the second two into a set of four 16th and the last two into a quintuplet of 16ths, which would look like this: The nested tuplet bar looks more like a bar of 3|4, but it moves at a faster rate than if the bar were written in 3|4 as opposed to a nested tuplet in a measure of 5|8. Click on the image below for a comparison of the measure in 5|8 followed immediately by the same rhythms in a bar of 3|4. In short, the purpose of this kind of rhythmic grouping is to manipulate the energy of a gesture, whether that energy is increasing, decreasing or becoming increasingly jerky and disorienting. Furthermore, by using these kinds of rhythmic groupings measure after measure a composer can create a waxing and waning sense of gestural motion while also obscuring any sense of rhythmic or metric regularity. All of this now leads us to a different question of why a composer would want to use these kinds of rhythms. We know from the paragraph above why they might be employed for the manipulation of time, but there is also the question of why they would be used on the basis of practicality. There’s the obvious argument of surface difficulty, not just in performing this kind of rhythm but also in just understanding how they work. These kinds of rhythms are rarely (if ever) talked about outside of composition seminars and lessons, so it is likely that many musicians never come into contact with nested tuplets, let alone find themselves in a situation in which they need to perform nested tuplets. So, given that these rhythms are seldom used (outside of the realm of “New Complexity” composers), not often taught, and are incredibly difficult to perform, why would anyone want to utilize this kind of rhythmic device in a piece? Won’t it limit the number of performers who will want to learn that piece, and in turn limit the number of performances the piece will receive? The simple answer to these questions is yes, writing difficult music (rhythmically speaking) will inevitably limit performance opportunities. However, I don’t feel that limited performance prospects should dissuade a composer from using these kinds of rhythms. The example above which compares the nested tuplet in 5|8 to the same rhythms in a bar of 3|4 demonstrates that in order to get the desired sense of energy in a gesture, and to squeeze a certain number of rhythmic impulses into a given amount of time one must write the rhythms in this way, even at the risk of the music being far more complex visually. The audience listening may not be able to hear that what they listening to is a complex grouping of nested rhythms, but what they will hear is the sense of energy gain or energy loss that the composer desires, and that communication is what is really important. One argument in defense of nested tuplets is that at the end of the day they are just rhythms. They are quantifiable, measurable rhythms. If one goes through the process of breaking down a nested grouping (as long and painful as it may be) then the rhythms can be learned, and eventually performed, given rest of the elements of the gesture are idiomatic for the instrument. The rhythms may be difficult to play and they may be even more difficult to read (and for the record they are also difficult to write), but that doesn’t mean that composers should shy away from using them, especially if it is the clearest way to notate the desired rhythmic gesture. There was a time when the rhythmic language of Debussy was highly complex. Elliott Carter’s system of metric modulation was a radical idea in the mid-20th century. But composers of the New Complexity “school” have been using these kinds of rhythmic devices since the early 1970s, and I think that after 45 years it’s time to stop looking at these rhythms with skepticism, confusion and disdain and accept nested tuplets as a viable tool for compositions of the 21st century. After all, it’s just a bunch of numbers, right!

18 Comments

paul

1/28/2016 10:34:07 am

Hi. What software did you use to get the rhythms to play audibly? Thanks.

Reply

Jon

9/14/2016 03:14:09 pm

Hi Paul. Sorry for the late response. I used Finale (actually Finale 2007) for all of the notation. Finale will handle playback of nested tuplets with no issues. It's a bit of a pain to create them because you need to first create the top-level tuplet and put in your notes up to the start of the second-level tuplet. Put in rests as place-holders and click the first rest and create your second-level tuplet, enter your notes and move on with the rest of the tuplet. If you have any other questions just shoot me an email at [email protected] and I can help you out. Thanks for reading!

Reply

Jared Simon

1/20/2017 10:01:33 am

I am a drummer who is absolutely in love with this type of stuff. Just seeing these rhythms notated brings me to a state of bliss!

Reply

Jon

1/20/2017 10:11:32 am

Thanks for the comment, Jared! It's good to know there are people who approach this kind of music and rhythmic structures from a place of intrigue and curiosity.

Reply

Vick

4/5/2017 03:59:57 pm

I'm very interested in learning about nested tuplets. I understand what it is, but the notation makes no sense to me. For example what does 6:5 mean or 5:4?

Reply

Jon

4/5/2017 04:02:57 pm

Hi Vick. I'm more than happy to talk about this in more detail. Shoot me an email at [email protected] I'll fill you in.

Reply

Benji

5/26/2017 03:24:39 pm

I understand 6:5 means playing 6 base notes over the period of 5. Your nested tuplets are described as 3 and 5, does that imply 3:2 and 5:2? This would make sense since 3:2, 2:2, 5:2 adds up to the initial 6 base notes.

Reply

Jon

8/14/2017 10:50:43 pm

Yes, that's correct. What makes the two examples different is that the top example with the nested tuplet contains 6 eighth notes over the span of 5 eighth notes (because it's a 5/8) bar. The bottom example is the same written rhythm in a 3/4 bar, which already contains 6 evenly spaced eighth notes. It sounds like you understand from the way you described it in your comment.

Reply

Kyle

8/14/2017 08:47:59 pm

Have you ever studied any of the scores of Kaikhosru Sorabji? It seems like virtually all of his compositions are chock full of nested tuplets, yet I don't think he identified with New Complexity. Perhaps NC composers were inspired by his work?

Reply

Jon

8/14/2017 10:56:31 pm

I wasn't familiar with his work before tonight. After a quick look I saw a lot of tuplets (especially 4:3) but no nested tuplets yet. I'll keep exploring though. I'm sure Ferneyhough and Finnish were at least familiar with him since he was an English composer. Thanks for the tip!

Reply

Ralph Turner

5/20/2019 03:29:36 pm

Hi Jon, I’ve been playing these types of rhythms for many years now, without really understanding the nested tuplet theory you describe. My usual way of deciphering the rhythms within rhythms phrases was to separate the different subdivisions of the first level tuplet that you describe and learn each of them as one beat of a bar of 4. Then I would practice the phrase until I could fit it into the correct number of beats, I’d appreciate your thoughts on this approach.

Reply

Tħinġine

8/18/2020 11:59:44 am

can I use the melody for a piece?

Reply

Jon Fielder

8/19/2020 09:03:51 pm

Hi Thingine! Thank you for reading and for your interest in the melody. However, I would prefer you not use it for one of your pieces, as it is a melody I've already used in one of my own pieces. That said, with some slight modifications you could get a nearly identical melody. If it's the contour and gestural energy you like then a very similar melody could also work.

Reply

Thingine (Ethan)

6/16/2021 09:35:38 am

this was very interesting!

Reply

Michael Shields

3/9/2022 12:09:56 pm

Thank you for this tutorial Jon. I found your article after reading an article about Steve Vai. I have always been awed by Vai's and Zappa's rhythmic compositions and want to learn how to use these devices. Please offer any advise you have concerning further study in this area. Thank you for your response!

Reply

Jon

3/10/2022 08:45:30 am

Hi Michael! Thanks for commenting, and I can't tell you how much it means that you got here by way of Steve Vai. He's one of my favorite musicians and he and Zappa are primarily why I became a composer. I'd be happy to talk about this kind of stuff with you more or point you to some resources. Shoot me an email at [email protected] and let me know what you need!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

The "Direct Sound" Page is dedicated to general blog posts and discussions. Various topics are covered here.

Full Directory of Articles |