Black Sheep Contemporary Ensemble Black Sheep Contemporary Ensemble

What is the Black Sheep Contemporary Ensemble?

Black Sheep Contemporary Ensemble is a new music group focused on performing music by living composers, commissioning new works, interdisciplinary collaboration, and educating audiences about new music. Since forming in 2014, the ensemble has performed with visual artists, dancers, and choreographers to create new, often site specific works. BSCE has commissioned and premiered multiple new pieces while also giving repeat performances to works by living composers worldwide. Our instrumentation is fluid, consisting of our four core members Nicole DeMaio, Bradley Frizzell, Emma Staudacher, and Aaron Smith, alongside a varying number of invited guests. We alter the instrumentation of the group based on the specific needs of each performance, but you’re likely to see several guests join us for multiple performances within a season. All of our core members perform with the ensemble and also hold administrative positions, like Nicole who is our Director and Bradley who runs our Outreach Program. How did you all meet and being playing music together? The ensemble actually first started out as a bass clarinet and tuba duo with myself (Nicole) and Liam Sheehy. We met at Montclair State University in New Jersey when I was working on my bachelors degree and Liam was getting his masters. After graduation we both ended up moving to Boston. I was starting my masters at The Boston Conservatory and Liam, a Massachusetts native, moved back and started working in the city. When I started at BoCo, I quickly realized I wouldn’t have many performance opportunities since I was majoring in composition. I decided the best solution was to start my own group, and thus, Black Sheep was born. I asked Liam to join because I knew he was interested in contemporary music and I liked the unusual instrument combination. Our first concert involved commissioning a handful of BoCo composition students to write us pieces and was held in one of the school’s performance halls. After graduating, I decided to expand the duo into an ensemble to help avoid always needing to commission new pieces. Emma and I both graduated together, and I knew that she was interested in new music, so she was the first person that I asked to become a core member. Bradley performed with us at our first Boston Sculptors Gallery show in 2016, and became a member and our Community Outreach Coordinator shortly afterwards. Aaron and I met at a BSO concert, and now handles all of our technology and viola related needs. How do you go about programming? Do you commission a lot of new works in addition to existing pieces in the repertoire? Programming for our ensemble varies from selecting works for a traditional concert to composing all new music for a site-specific event. For our concerts, we used to hold Calls for Submissions throughout the year, but have since switched to an open submission forum that any composer can add to for free. We accept a variety of new works, previously performed pieces, and proposals for new pieces to be written for us. One of our goals is to program works that have already been performed, as many other groups focus primarily on premiers and commissions. To decide the instrumentation for a concert we first pick one larger work, one that includes some of our core member’s instruments, and then select other pieces based on that. Do you have any other special considerations in terms of programming? Do you like to perform at certain kinds of venues, involve technology and other media, etc.? Our programming varies from concert to concert. A lot of what we do is based on the space and the type of concert we want to put on. Some concerts feature traditionally composed pieces while other concerts will be programmed with electronics or other non-traditional aspects in mind. We have done performances featuring things like sculptures, interactive light suits, dancers, iPads that audience members can control, or improvisation. Sometimes the music we pick is based off of artwork inside the space we are performing, or we might focus on a particular composer’s body of works that we feel have been overlooked. Intersectionality and representation of marginalized voices is a topic (and issue) of contemporary music that is being discussed more these days. How do you feel about this, and is this a concern (or perhaps a goal) in terms of concert programming and commissioning? We feel that the representation of marginalized voices in music is a subject that everyone should be concerned about. So many chamber groups and orchestras only play music from a small category of composers. Black Sheep Contemporary Ensemble has made it one of our priorities to be a champion for women and POC in contemporary classical music. There are many wonderful voices out there that just need a proper opportunity to be heard. We recently commissioned four composers to write new works for our core instrumentation, three of whom identify as female. Your website mentions that you also enjoy interdisciplinary collaboration. Could you talk a little more about that and maybe about some of the work that has come from those projects? Many of our projects include interdisciplinary collaboration. One of our most frequented venues is Boston Sculptors Gallery. The performances always combine sculpture, music dance, choreography, and composition. We perform music specially composed for the occasion, written by members of the ensemble. All of the music is based off of the sculptures that inhabited the space. We then in turn created choreography that connected with the music and artwork. After our first performance at BSG, we’ve ended up performing at several more galleries throughout Boston and have expanded to New Jersey and Rhode Island venues as well. One main goal of our ensemble is to create true interdisciplinary collaborations. We have no wish to create concerts that are just musicians playing music next to dancers with paintings in the background. That isn’t really collaboration, it’s just three things happening at the same time. We create works in which all the arts are influencing each other. Often times we even switch roles between the performers; musicians dance while playing, dancers sing while dancing, and everyone helps compose and choreograph. If we are performing with visual artists we try to keep an open dialogue with them during the compositional process to ensure that there is a mutual understanding of the artwork and the ensuing composition. What, as an ensemble, has been a highlight of your career performing together? One of our favorite moments came from our concert back in December of 2018. The crowd for that show was fairly small, and we felt a little disappointed that more people hadn’t come out. After the performance, an audience member came up to us and complimented us on our programming choices and the effectiveness of our works that incorporated dance and visual art. He said something along the lines of “I’ve been following you guys online for a while, and what I saw tonight was really unique. There’s a lot of new music happening in Boston and this was refreshingly different.” Getting feedback like that makes you feel proud of what you’ve invested your time into. We loved knowing our audience, no matter how small, enjoyed what they had seen and heard that evening. Do you have any long-term major goals you are working towards? Maybe a large-scale collaboration with a composer, concert series, or something else entirely? We are currently working on commissioning a new micro-opera to be paired with one that is already composed. We’re aiming to have the performances in Spring of 2021. Our big hope is to perform the work both in Boston and New York. Our biggest struggle has been to get enough funding to travel and perform the same musical program multiple times. We are also in the middle of a collaboration with an author to create a new piece for children through our Community Outreach sector, but can’t talk details just yet. What projects do you have in the works right now? Our focus now is on the other two performances this season, one of which will be in Providence. I’ll be working with Aaron and Bradley to create a new, evening length work which will be premiered at AS220 on March 8th at 2:00pm. We’re hoping to bring that performance to NYC, NJ, and beyond. We’ll also be presenting a traditional concert of new works with exact dates and times to be announced soon. Again, if we can get the funding, this concert will happen several times in multiple locations. Follow the links below for more information about Black Sheep Contemporary Ensemble: Website: https://www.blacksheepcontemporary.com/ Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCAG3_uoJpmyvuucGjmI0rKQ/videos Below are video samples of Black Sheep Contemporary Ensemble

Short collage video of highlight performances by BSCE

Extended video of performance at the Boston Sculptures Gallery in 2018

0 Comments

What originally drew you want to pursue composition?

As a child, I got into music in kindergarten by perfectly playing melodies back on a piano after my teacher played them. I always had a natural ear for music, and I always loved creating things; I knit, crochet, cook, bake, and growing up learning these things, I quite often bent the rules. My first improvisations happened at a young age. Then, with my first long-term piano teacher at the age of 10, I learned rudimentary music theory, which lead me to compose small pieces in the style of Chopin and Debussy (my two favorites at the time). I attended Apple Hill for chamber music camp, and composed pieces for friends there, as well as some solo piano works and a PDQ Bach-esque piece called Mozart’s Piano Concerto for Orchestra. Then, during my undergrad, a composition major student (fellow freshman) encouraged me to double major in composition, which I did, and eventually dropped the piano major. I remember during my freshman year debating whether or not I should take composing more seriously. I used to, on my own, spend about an hour or 2 in the music library after a bi-weekly class listening to music with scores. When I got to Gruppen by Stockhausen, I was COMPLETELY blown away. That was the moment where I thought to myself, I really want to do this. You’re also very active as a performer. How has your work in performance influenced your approach to composition? Or do you see these as separate practices? For the most part, I see these as separate practices. I even have a weird split personality when it comes to these different activities, often criticizing my compositions when I perform them. But nothing is totally separate, and I think some of my approach to consciously writing-in specific types of performance freedoms in my works comes from my performing personality wanting these freedoms. Additionally, my penchant for idiomaticism may also come from my own desires for idiomaticism as a performer. I have played many works by young composers, and no matter how lovely a piece may be, if the piano part is not idiomatic, I feel some level of anger … mostly at the teacher of the composer! Your music is very eclectic in terms of style and genre. Can you talk a little about where you draw inspiration, and what drives you to create the music you write? My inspiration comes mostly from my life experience. I was born in Virginia, but raised in Rhode Island, then spent significant time in Boston, then Boulder, and now I live in the Netherlands. However, I travel often, though, and I always seem to have multiple homes. This idea of multiple homes and multiple loves is really a metaphor for what and how I compose. Growing up, my dad made me love Motown, my mom made me love Gospel, my brother made me love Rap and Hip Hop, my friends made me love alternative rock and musical theater, and my own musical inclination as a pianist gravitated towards classical (from baroque to contemporary). I never had a permanent home in my musical interests, and this has translated to my own compositional interests and abilities. A quick glance at my repertoire reveals that I semi-regularly use visual art, American text, and the music or musical ideas of past composers for influence. I also like to use stories or ideas from marginalized communities, stories from past unsung heros, and I am now beginning to explore my own queer identity in my music and performances. I always hear a sensitivity and attention to timbre and instrumental color in your music (thinking specifically about Nicht Zart II: Hommage a Scelsi and Ohkyanoos). Is this a particular concern of yours during the composition process, or is it more a bi-product of counterpoint and instrumentation? Or something else entirely? This is a BIG concern of mine, and it makes me so happy that you pointed this out! In fact, during my music theory tutelage at BU and NEC, the relationship between orchestration/instrumental color/timbre and the overall musical journey of a piece was rarely discussed. When it was discussed, the teacher was a composer teaching a focused theory class or one of my private composition teachers. I guess I subliminally became frustrated with this lack of attention to color on an academic level, and said to myself, “what would happen if I stopped paying attention to rhythm, and focus almost obsessively on color?” This lead to me creating a type of notation (admittedly based on Lutoslawski’s box notation) that allows for a certain type of color manipulation, which you can hear in pieces like Midnight and the taking-in or 3 groups. This type of hyper-attention to color freed me up to compose the pieces that you mentioned above. Your bio places a great deal of emphasis on the importance of social justice and awareness in your music. Can you talk a little bit about what that means to you and how it manifests in your work as an artist? I have always been a political person, and my attention to and discussion of politics increased exponentially during my freshman year. I think 9/11 had a big impact on artists in that way, and even though 9/11 happened during my senior year of high school, the event was still discussed and argued over will into my senior year (and even to this day, for that matter). I remember hearing all of these 9/11 tribute pieces where a solo instrument or a chamber group would play pretty music, and I guess the listeners were supposed to be moved. I remember listening to tributes by more famous composers that took a similar approach, and I was left frustrated and empty. I wanted to be challenged. I wanted to be provoked. So, in 2004, I wrote my own 9/11 tribute piece, which was about the first world trade center bombing in 1993. It was around this time that I realized the power that music could have in conveying the gravity and the other complex identities of injustice, and since then that is how I have used music for social justice. You have a particular approach to creating music that is socially and politically engaging in which there is a clear statement, but I find is much more reflective and inquisitive than declarative of any position/thought. Is this intentional on your part? Definitely. When something important happens, it is easy to hear the story on the radio, read about it in the newspaper, online, or on social media, see it on the news, and just let it slip into the bromide of daily life. But certain things stick out to me. They gnaw at me. They scream at me to try to do something. And when I embark on a social justice project, it involves research, interviewing, intimating, imagining myself in another person’s shoes, arguing, writing … it is a process until I feel I am intellectually and emotionally ready to comment. Because I go through all this work, I want my audiences to have both an emotional and an intellectual experience. I like it when people think. I think people should think more, and music should make people think more. Especially social justice music. Can you also talk about your work with Castle of Our Skins - what is it, what is your involvement, etc.? Castle of our Skins is a concert and educational series organization dedicated to celebrating Black artistry through music. We produce educational programs as well as large-scale concert productions, community concerts, and other activities related to our mission. We also have had a research residency at the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago, and a college residency at Gettysburg College, and we are about to have another college residency at Brandeis University (sponsored by Music Unites Us) centered around the theme of being (musically) Black in Europe and Beyond. I am a co-founder, associate artistic director, composer-in-residence, and an occasional pianist. I have also given lectures to adults and younger students about the lives and music of Black composers, and composed the musical component to our most successful educational program entitled A Little History, which teaches children about the lives of 9 legendary figures of Black history through music. This year marks our fifth season, and it shows no signs of stopping! Much of my social justice work happens through Castle of our Skins, and creating this organization was a big step in coming into my own identity. It is the sole reason why I came to realize the severity of the lack of young, Black composers being represented in new music today, which is why I truly believe that my own existence is rare and - in many ways - an act of social justice. Do you have any interesting current or upcoming projects? Oh yes! I am very excited to be part of counter-tenor Carl Alexander’s Voic(ed) Project (https://voicedproject.com), where 15 Black composers have been commissioned to compose works that incorporate Mr. Alexander’s voice in some way. This project could benefit from grassroots fiscal support, and donations can be made here: https://voicedproject.com/support/ For this project, I am composing a work entitled Empathy I: Diamond Reynolds, which uses words that she said after her late partner Philando Castile was murdered. In January 2018, the tenor Anthony P. McGlaun (http://anthonypmcglaun.com) will premiere a new work for tenor and piano quartet called … her phantom happiness … , which uses poetry by Georgia Douglas Johnson. In Feburary 2018, I will attend the Escape-to-Create residency to focus on some song cycles I am composing in the big three European languages. I will start with the German cycle, which uses text by Louise Otto-Peters (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louise_Otto-Peters). During this residency, I will also give a community lecture and a concert featuring the music of Black composers. In the fall of 2018, NOISE-BRIDGE (http://noise-bridge.com) will premiere a commissioned work for voice, clarinets, and objects. This mega work (about 30 minutes) will be based on 9 visual artists and our (me and the ensemble) personal responses to these artists. Each of us will select three artists and respond to them in some way, and I will use the material to create a work. This will be one of my most exciting, collaborative works to date. I also have some performance projects/collaborations coming up, performing works by Renee Baker, Robert Schumann, and Ed Bland. And the inevitable final question, what are the top 5 pieces/songs that have had the most influence on your work as a musician? TOO MANY!! :-D If I were to pick a top five though … perhaps …

For more information about Anthony Green check out his website Below are some samples of Anthony's music

What made you want to pursue a career in music? More importantly, what interested you about being a composer?

I always had an interest in music from age 4, but it wasn’t until I took an orchestration class with Judith Lang Zaimont that I tried composing. It was more fun than practicing, and that was that! I also knew I would never be happy in a corporate office of any sort. Who were some of your earliest musical influences, composition or otherwise? As a small child, I would always play the same two songs in the jukebox at the truckstop diner in town: Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” and Pink Floyd’s “Money,” in that order. The Pixies and 90’s industrial music taught me about dissonance and timbre as an expressive force. Aphex Twin sparked my interest in electronic music and production. Before I started composing, I wrote poetry and short stories, so that carried forward to an interest in songwriting when I started writing music. Can you talk a little bit (generally) about your music. Where do you find inspiration for new pieces and what is the general process you take when composing? My process is intuitive in that I start at the beginning of the piece and write to the end, often developing ideas as “organically” as possible, with lots of editing along the way so the pacing and balance is right. I tend to be slow to start a piece, then get obsessed once I figure out where it might be going. Often marathon sessions are undertaken out of necessity to meet a deadline or when a break in the schedule allows for extended creative time to start and finish a project. I generally draw inspiration from my other non-musical interests: sociopolitical and environment issues, nature, mythology, spirituality, the intersection between art and science. It’s an opportunity to start conversations. For example, little tiny stone, full of blue fire is a quartet inspired by the discovery a new pigment in a very hot fire, YInMn blue, which led me to discover a poem by Dorothea Lasky (“Beyond the Blue Seas”) that deals with similar ideas, but in more personal terms. River Rising was inspired by the video I saw of the 2011 tsunami in Japan and the consequences of climage change. My first experiences with your music were pieces for instruments and electronics. When did you begin working with electronics and implementing that in your pieces for live performers? I took Evan Chambers’s electronic music seminar as a masters student at the University of Michigan without much initial interest in the subject. After one semester of learning to listen entirely differently—to appreciate that music is far more than notes and rhythms—I was excited to have limitless possibilities and absolute control over interpretation, timbre, and spatialization. Gaia was the first piece I wrote in that class. Its source material was one four-note djembe sample that I processed a million different ways. It took me six months to write, partially because I didn’t know there was a grid function in ProTools, so I lined up all the individual hits by ear to make various rhythms. It was the first piece I ever heard premiered as a young composer, spatialized in 8 channels in a big auditorium, with sound flying all over the room creating a sense of physicality and power I hadn’t experienced before… and I was hooked. When my friend Lisa Raschiatore asked for a piece, I wrote for clarinet and fixed media (Ultraviolet) and learned a lot about technical needs of the performer in trying to sync up with technology. I learned to approach the electronics as I would any other instrument: they can play a supporting role or take the lead, be in counterpoint or harmony with the solo line, tacet to allow for acoustic moments or take a solo while the performers stop. Orchestrationally, it feels the same as writing for any other ensemble, but now any sound I can imagine and create is possible. Do you work primarily with fixed electronics or do you also work with live processing of instruments? I’ve always been drawn to fixed media because I felt I had a better ability to control every last detail (and there are tons of them) with less of a possiblity of computers crashing. In more recent works, I’ve used live processing to color the solo line, to change its relationship to the fixed media part, to allow for freedom in performance. When Lilit Hartunian requested a looping piece (Alone Together) on a quick deadline, I played around in Ableton and a piece appeared within the day. I try to use whatever tool works best. You’re also active as a performer (pianist with Verdant Vibes and Hotel Elefant). Can you talk a little about your work as a performer. I started college as a performance major and when I decided to pursue composition instead, I literally shifted my time spent practicing to time spent writing. I would play my own pieces here and there, but it wasn’t until Hotel Elefant invited me to play with their newly-formed ensemble that I started performing regularly again. When job opportunities almost lured me away from Providence, but then didn’t, I felt motivated to create my own gigs as a composer/performer locally, so Jacob Richman and I started Verdant Vibes with a seed grant from the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. We’re in our third season and have performed over 40 pieces by an array of living composers from around the area and the world. It’s rewarding to create jobs for other people and bring this kind of art to the community. How does performing influence your approach to composition? Do you keep these separate or do you feel that one is always influencing the other? Performing makes me more aware of the physicality of the music—what it feels like to interpret a score or how people breathe and interact expressively on stage. My ears are continuously learning more about what works and what doesn’t, and how we physiologically respond to sound and ideas. It allows me a better understanding of the sounds I want to hear when I compose and how to make that happen. You’re also involved with other projects in various capacities (performer, composer, lecturer, artistic director) and have worked in multimedia. Can you talk a little bit about your interests in collaborative and/or cross-disciplinary and multimedia works? The arts community in Providence is exceptional and has been a valuable resource for finding collaborators and friends. Working with people possesing different skills and ideas has allowed me to create projects I never would have dreamed up alone. I write and perform with Meridian Project, a multimedia performance group exploring topics in astrophysics and cosmology. We often perform at plantariums and observatories as a collaboration between musicians, scientists, visual artists, and audience participation on topics like dark matter detection, comets and meteors, the sun and moon. Half the band lives in Chicago now, so we’re working on finding residencies to have time to create a new project in collaboration with scientists at LIGO. I worked with video artist and composer/performer Alex Dupuis on a video to accompany for Anna Atkins and invited dancer Meg Sullivan to improvise movement. Previous projects with Jacob Richman have included playing accordion in a multimedia dance piece at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and a multimedia roving opera about an unsolved murder mystery in Rhode Island. In 2011, I worked with a group of local artists under the moniker Awesome Collective to create a roving performance piece Mercy Brown and the Devil’s Footprint at a park in Providence exploring local folklore that involved theatre, installation, dance, music, shadow puppetry, and animation. I am also co-music director of Tenderloin Opera Company, a homeless advocacy music/theatre group I’ve been involved with for 7 years. We meet weekly before a community meal and devise characters and scenes that become an opera over the course of the year, which we set to music and sing/perform together in May. We also perform at meal sites, protests, arts events, and schools to raise awareness and support to address issues they face like access to public transportation, benefits, and health care and end homelessness. Do you have any upcoming projects you would like to talk about? I just finished a piece for bass clarinet/percussion duo Transient Canvas called Year Without A Summer that they will be touring around the country this season as part of an electroacoustic program. I have an orchestra piece in the works commissioned by Rhode Island College and a duo for piano/bass/electronics to be premiered this spring with Verdant Vibes. It’s application season, so various other things have been dreamed up, and perhaps they will come to fruition. And, finally, the list. What are the top 5 pieces/songs that inspired your most throughout your musical career. This is hard, and I am indecisive, but albums I listened to a bazillion times in my formative years seem most relevant: Nine Inch Nails — Downward Spiral Björk — Debut The Cure — Wish Stevie Wonder — Greatest Hits (any of them) Aphex Twin — Selected Ambient Works Vol.1 & 2 For more information about Kirsten Volness, her music and other activities check out her website: www.kirstenvolness.com/ Below are some examples of Kirsten's work: Volness — for Anna Atkins from Jacob Richman on Vimeo.

This week I sat down with Amanda DeBoer-Bartlett, one of the organizers of the Omaha Under the Radar festival, to talk about this exciting event, its history, and what you can expect from the 2017 festival, going on July 5-8.

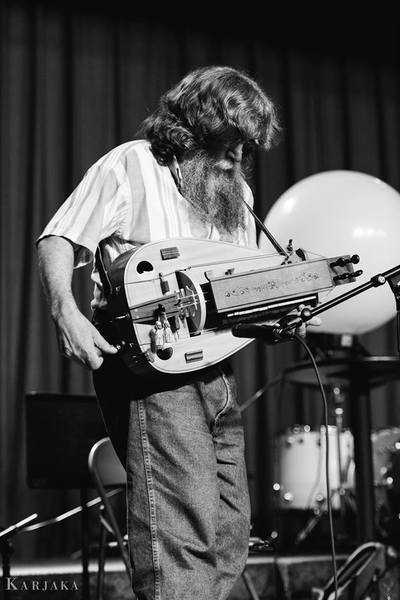

How did Omaha Under the Radar get started and who all is involved behind the scenes? After graduating from BGSU, I moved back to Omaha to be with my husband, who has a job here. I had organized a couple festival-like events before Omaha Under the Radar that were basically beta OUTR, so I had a little bit of experience before I decided to move operations here. What I learned from my previous events is that it is infinitely easier and more meaningful (for me, at least) to organize this event in the city where I live and have roots. The organizing team is really the heart of this event. All three of us are from Omaha, so we’re very much pretty tied to this place and have a stake in contributing to the cultural landscape. In general, we’re all equally in charge of programming and managing applications, venue selection and artistic direction. Stacey Barelos is a composer and pianist who grew up and currently lives in Omaha. She runs our outreach and education branch, including SOUNDRY Workshop, she manages rehearsals and logistics for our large ensemble pieces, and is developing our new, year-round concert series presented by KANEKO. Aubrey Byerly is a composer and bassoonist based in California. She spent her childhood in Omaha and returns every year for the festival. She runs financials and does a lot of contracting and personnel logistics, and is also helping with programming for our concert series at KANEKO. What would you say is the primary goal of this festival, and what are some things you would like to plan for future festivals? I could quote our mission statement...but basically, we want to present artists who are taking risks and challenging the status quo (both their own and others’), and who are seeking deep connection with the people and communities around them. We want to be an inviting presence in the Midwest that encourages audiences to think deeply about art and form strong opinions about this work. We want to be eclectic, and to create complex programs that offer divergent experiences within a single event. Basically, we want to challenge people and bring people together! And we want to be challenged! The best moments are when we, the organizers, are completely taken aback and surprised by an artist. I mean, we planned it, we should be ready for it all, but we never are! Long-winded questions here, but as a composer (and former OUR festival attendee), I’ve always loved that Omaha seems to be focused more toward the performative/performance related aspects of the music. For example, conferences like SCI, the BGSU New Music Festival, June In Buffalo, the ACF Festival of Contemporary Music, etc. are all very composer-centric. Composers submit pieces or are invited to attend, the concerts are organized around presenting the composers’ music, there is often a featured composer, the list goes on. Omaha seems to take a different approach and asks artists (of all kinds) to submit projects or full 30-minute sets of music, sometimes by various composers or a single composer. The focus is shifted to make the performer as important as the composer. Is there a reason you took this approach to programming and curating? I think we originally conceived of it more as a “fringe” like festival, so those are really geared toward the performer. Every year, however, composers and creators who are not performing do attend, which is fantastic. We love that. The events you mention are “conferences” in my mind, and are really geared toward helping the people attending to learn new skills or research, network and build their resume. There is plenty of that happening at Omaha Under the Radar, but the primary focus is getting these artists in front of Omaha audiences and building connections between audience and artist. If artists network with each other, that’s great! But the public performance side of this is the most essential element. I have found, in attending and participating in plenty of conference situations, that I have definitely enjoyed them and benefited greatly from them, but that they often feel pretty disconnected from the cities and communities where they are held. We try to integrate the event into the city as much as possible, and for us, that’s all about building the local audience. Every year I’ve attended OUR it seems the festival grows and spreads across the city with more events and more venues. Is that trend continuing this year? We actually cut back a little! Our most common critique is that people didn’t like that events overlapped in the schedule. They didn’t want to have to choose between acts. We didn’t want to add a day to the schedule, so we cut a couple events. We went from about 40 acts to about 30, and we spaced things out a little more. Honestly, it’s for the best. By the time you watch that many performances, your brain is totally fried! If we had it in us, we would cut it down to 20 acts and be even more selective, but we just love these artists so damn much. It’s heart-wrenching having to turn people away every year. I wish we could accept 100 artists! So no, we aren’t expanding, but we are becoming more and more selective every year. Is there any kind of theme to this year’s festival? Not really. We don’t want to impose that strong of a curatorial presence. All of the artists have complete control over their individual programs, and we want to keep it that way. We basically just tell them how long their set is, and then let them to it. We obviously have to choose which artists to put together on which events, and that often comes down to schedules, tech, logistics, boring stuff. Will there be any large or special events for this year’s festival? Yup! We’re presenting “Eight Songs for a Mad King” by Peter Maxwell Davies. John Pearse is singing the role of King George III, and we have an ensemble of fantastic musicians filling out the ensemble. I can’t wait for this one. It’s our first time hiring a costumer/designer and stage director, and it’s going to be bonkers. So much time, effort and money goes into planning an event like Omaha Under the Radar. What do you find to be the most rewarding takeaway from organizing an event like this? Dang. So much. Seeing audiences return year after year, and watching them become more critical, discerning, and inspired at each festival. The fact that my mom is developing strong opinions about contemporary performance work. Seeing the national network of contemporary performers come together in my hometown. Hearing from Omaha artists that this festival inspired them to start a project or group, encouraged them to take a risk, or helped them take themselves seriously as an artist...it’s actually pretty overwhelming and I’m tearing up writing this. Sorry not sorry. Will any portion of the festival be live-streamed so that people who can’t attend the festival in person can at least see some portion of it? Hmm...maybe...I’ll get back to you! And if there is anything else you would like to say about the festival, its history, what can be expected this year, etc. please feel free to share. There is a massive amount of love put into this festival, for the artists, for Omaha, and for this work. Thanks to everyone who supports us, both at the festival and from afar! And major love to anyone who is doing similar work in parallel, non-coastal locations <3 For more information about the Omaha Under the Radar festival, checkout their website and Facebook page for this year's festival. Below is a video compilation of last year's festival (video by Philip Kolbo), as well as some images from previous festivals (all photography by Karjaka Studios).

What made you want to pursue music as a career?

The sound of the clarinet. I heard it in the Beatles song “When I’m 64” when I was a kid and really was fascinated. Maybe more formative: I have this memory of seeing a performance of Sibelius’s Swan of Tuonela by the Savannah Symphony Orchestra when I was like 13. It’s hard to recollect precisely, I only know that the experience was powerful and new and elusive. Something about the way the string chords made my body feel, like I was enveloped in sound. It was some sort of complete experience, a bodily one, a temporal one, an emotional one, a generally overwhelming one. This may sound exaggerated or self-involved, but it was like being born; or at least the memory of the experience makes me want to use language like that. It lives in my memory as a kind of traumatic thing happening to my personhood. And it made me drawn to musical experiences like that (which a bit ironic, since I tend to be risk-averse; but maybe doing music is my way of sublimating that impulse). Along those lines, I recall in college reading the ancient Greek text “On the Sublime” by Longinus and relating to it strongly. The aesthetic category of the sublime remains an area of great interest for me today. More specifically, what got you interested in conducting? And even more specifically, what do you love about conducting new music? Thanks for asking this question; it’s something I’ve thought a lot about. My initial impulse to be a conductor was probably ego-driven, as I imagine many people’s choices about their instruments/fields are. Though it’s hard to reconstruct accurately, I bet that I fantasized that conducting, would, you know, make me feel good. Is that right? Like, it seemed like the conductor was the one having the most fun, and that’s the person I wanted to be. As my life has gone on, my attitude towards the role of the conductor has evolved considerably, and no doubt will continue to do so. And this lives in a symbiotic relationship with my interest in conducting new music. While conductors are in many cases necessary and sometimes even helpful, I’ve also seen conductors often get in the way or become (much, occasionally) more trouble than they’re worth. While this can happen in obvious ways—we all know the trope of the tyrannical, high-maintenance, diva-type conductor, one who exercises power simply for the sake of exercising it—it can happen subtly as well. Conductors can both aide musicians, but also impinge on their autonomy in long-term and detrimental ways. I think this really works on all levels: from how one thinks about programming to how one runs rehearsals to the actual conducting technique itself. Conductors that are hard to play for—and I think all instrumentalists and singers know what I mean by that—really do impose upon a performer’s personal musicianship in a way that is harmful, even if the affects are only perceptible over time. I think there’s a reason I felt a strong connection with the composer mathias spahlinger when I met him. He has a work from the 1993 called vorschläge/konzepte zur ver(über)flüssigung der funktion des komponisten (hard to translate without sounding fancy, but I’ll do my best: propositions/concepts on the liquidation/redundancy of the function of the composer). I get the sense that for both him and I, the goal is our own elimination. The utopian goal of the composer is to make it so everyone composes music for themselves (Attali has written about this as well, and I sort-of review a performance along those lines, that you can read about here); similarly, for a conductor it should be for people not to need conductors. I don’t think this has a Cage-ian flavor as such, but a more straightforwardly politically emancipatory one. Though I don’t want to make my claims too grandiose; what I do is limited in scope and in any case I don’t expect a utopia to arrive, as such. (And I’m not even sure I have a clear idea of what I mean by utopia.) But if we can slowly and asymptotically approach it, well, I can be part of that. I admit that that seems far-fetched in 2017’s political climate. So so so very important to me is how I relate to the musicians I conduct. If it’s not an actually collaborative atmosphere, I just don’t want to do it. With the Dal Niente musicians it’s easy—they give me plenty of pushback when they don’t like stuff I do, and they are very independent and autonomous musicians. With orchestras, though, sometimes, it can be a challenge. Some (certainly not all) musicians really are habituated to simply just doing whatever a conductor says, and it can cause discomfort when they are asked to have an opinion. Well, really it’s a continuum—some musicians want to be super independent, and some just want to be blue collar workers, and there’s everything in between. But I strive to do what I can to be some part of helping them be able to self-realize better; in some cases it’s a lot, in some cases it’s not much. But it’s a process, and it’s important that it continues, and that I’m conscious of it all the time, and that I’m conscious of my own limitations. I’m sure I fuck up a lot. Do you do much performing, or is your work primarily rooted in conducting? Well, if were to self-identify in a capitalist-division-of-labor type way, I would say I’m a conductor first, a teacher second, and a writer third. But I’d immediately problematize this statement, and say that really teaching is part of my artistic work. While I do strive to make sure that my students are appropriately trained to be professionals—that they can get orchestra jobs if they want to work at that, say—it’s much more important to me for them be artists and people who can work on their own self-fulfillment. I’d rather them be happy, or approach happiness, than have a so-called “good job” that they actually hate. Sometimes this means being super real with them about their chances of success in fields where things are tough; sometimes it means encouraging them to take risks I know they want to take; sometimes it means introducing them to repertoire, or coaching their chamber music group; sometimes it means putting them in an uncomfortable position with music they don’t like. Honestly, I find teaching to be much harder than conducting, and it’s a minefield of artistic and ethical and financial quandaries; I’m not a natural at it, so spend a lot of time second-guessing myself. I tend to hope this second-guess-y nature is a net positive for me. Do you assist with the concert organizing and repertoire selection for Dal Niente? Yes, but I should hastily add that I am not the artistic director of Dal Niente, and that it doesn’t have an artistic director, and that it will never have an artistic director. ...something about power and corruption and absolute power and absolute corruption… The programming process for us is complex and messy and takes a long time. There is a sort of programming committee, but the players have plenty to say if they want to do so. I definitely have an agenda of my own, one that I try not to hide: I’m interested in—depending on how you look at it and how you define words—canon expansion or canon destruction. By which I mean not that we (I’ll leave “we” intentionally undefined) shouldn’t play old (or even last-50-years or contemporary-but-conservative) music by dead white guys, but that we must make sure to have complex and nuanced understanding of why we do so and why it is/was influential; while at the same making sure to understand that such music is highly historically contingent and doesn’t necessarily have to be played; while at the time trying to make so that music we play is representative; while at the same time not reducing programming to a question of identity politics. Basically: what was or is or could be or will be music is huge; and it’s getting huger, and I’m interested in feeling as much of that hugeningness as possible. What is one of your most memorable moments as a conductor? The bit in Haas’s in vain where I don’t conduct, lolz. The bit where I’m just standing on stage in the dark while everyone else plays. It’s electrifying, terrifying; sublime, to use the word I did earlier. (sidebar from Jon: Dal Niente’s February 28, 2013 performance of Haas’ in vain is one of my most cherished live performances to date. I couldn’t be there in person [unfortunately], but watched a live stream and to this day rewatch the video here) You've also done some writing on various topics of new music. What drives you to write and what are some of your primary topics of interest? I think there are many people who are doing terrific (non-academic, say) writing on music these days and in the very recent past; the following come to mind in no particular order: Doyle Armbrust, Ellen McSweeney, Deidre Huckabay (who, full disclosure, is my partner), Steve Smith, Ray Evanoff, Marek Poliks, Ian Power. Cacophony Magazine, an heroic Chicago DIY effort (started by Bethany Younge and Lia Kohl, currently run by Jill DeGroot and Kelley Sheehan), is trying very hard to cultivate a sort of thoughtful online discourse in this city. (I intentionally don’t mention a bunch of brilliant young scholars working on new music, which is a different and v exciting topic.) I note that almost of my favorite non-academic writers on music, though, are not journalists in mainstream media publications. I don’t think I’m saying anything too controversial by asserting that discourse one reads in such publications (newspapers, say) about classical and new music has been frustrating in recent years. (...hastening to add notable exceptions who do terrific work, and who may be responding to this very problem: Will Robin (with his various hats), Anne Midgette, Mark Swed, Zachary Woolfe among others.) Perhaps we’re at a crossroads. We might genuinely question the relevance and purpose of the concert review as we’ve inherited it. While there are some good exemplars, there are many more that are problematic: sometimes boring or unhelpful, occasionally actually detrimental. For standard rep concerts, reviews might be, say, vague speculations about what a conductor might have thought, mixed with congratulatory or cutting remarks about a performer; for new music shows, reviews are often one paragraph about each piece, with some descriptive language and then an evaluation (either that the reviewer liked it or didn’t like it). I've read many reviews during which I've asked myself why it was written, and what it contributes to the discourse, and I end up thinking that it's actually just an unconscious expressions of neoliberal ideology—where there's a tacit commodification of a musical experience, a turning the concert into an athletic event. Such writings reify the music and the performers, and really strip away something meaningful about their listening experience and their humanity. The performers often feel misunderstood or patronized. And what does someone reading a review after the fact really get out of it besides gossip? I’m intentionally speaking in generalities by using language I have above, “many reviews,” “reviews are often,” that sort of thing, because I’m not trying to call people out. I can only assume that everyone’s doing the best with what they have and I don’t mean to be insulting. It’s more that I wish music journalists who write like this, and who have jobs at newspapers and such, would self-reflect honestly. Written, non-academic mainstream media discourse about music is a hugely problematic aspect of our culture; and I’d speculate that some sense of this problem drives the people I mentioned above to do the excellent work they do. Put yet more positively: there are so many musicians and composers and writers in this rapidly changing field who are doing actually genuinely mega-exciting work. So how do we understand and interpret this work, and how do we construe its meaning, what does it do in our lives? It seems to me that the role of the critic in these questions is central to this ecosystem. While it’s deeply frustrating to see a poverty of discourse in some places (especially publications with money and reputation and readership), it’s life-affirming to see to see it develop richly in others. Since actually you asked about me, and I didn’t answer your questions, I’d say this: I wrote mostly because I enjoy writing and I have stuff to say. I’m a bit uncertain and insecure about my writing, but I think Deidre actually described my attitude accurately: that I seem to view it as an act of good citizenship. I think this is right. I feel a duty to communicate in every way I know how, and I’m ok being wrong about stuff. This is a huge topic with no easy answer, but what direction do you see contemporary music going in the 21st century? Or is it proceeding in any clear direction? I feel like reading the last chapter of Attali’s Noise, the one about composition, is a good place to start. It’s pretty hard to hazard a guess what going to happen, but I will say this: I have been really heartened by the sometimes angry sometimes perplexed but very energetic reaction of musicians to the terrible, terrible political situation in this country. I find myself almost saying something like: I hope this leads to a more engaged, political sort of art. But I don’t think that’s quite accurate; rather, art is instantiated politics; it is always already political. Maybe what I feel is new music waking up to that realization. It would irresponsible to make a self-important or aggrandizing claim about new music—that it can advance a concrete political cause effectively—but I do want think that how we conduct ourselves, how we interpret the music we make, and how we interact with our audiences, really does have transformative potential in some areas. Culture is a big thing; music is a part of it, and let’s not pretend that it’s above or removed. Do you have any exciting upcoming events or projects? YES, YES I DO YES VERY EXCITED OMG!!!! We’re releasing the record we are finishing of George Lewis’s pieces at the Art Institute of Chicago in a multi-day event in September. In October, we’re doing two new monodramas by Eliza Brown and Katie Young as part of our Staged series. I think these are two of the most exciting composers working today, and I think these pieces will do things that will feel strong and real. More immediately, I’m looking forward to being resident conductor of the soundSCAPE festival in Italy this June and July. Longer term, I’m lucky enough to have just been granted tenure at DePaul. I’m still trying to process what exactly that means, and how I might best use the security of such a position for the best artistic and education ends. I have programming ideas, of course, but I bet I can do better. And for the always-necessary top 5 list: what are the top 5 pieces/albums/scores that have been your biggest influences over the years? 1) Beethoven’s Eroica symphony: in a sense, I use this as a yardstick for myself; I’ve known this piece for a long time, and it’s never lost its power over me, though my reading of it has changed a lot. 2) Mahler’s 9th symphony. 3) Some Shostakovich pieces, say the 4th and 5th symphonies, but maybe not for the reasons you might think. It’s a very personal association: it’s from when I was 16-17 years old, studying with Prof. Musin in St. Petersburg, and remembering how Musin conducted that music; he was just so good at embodying it, like really “em-bodying” it, having it in his body. 4) Ligeti’s Lontano was a piece that I encountered early in my life on Chicago Symphony radio broadcast, and maybe was actually my introduction to doing such a thing with an orchestra; and it’s a piece I’ve returned to frequently over the years. 5) Hard to identify just one work, but George’s Lewis’s music and thought—particularly how broadly he construes the practice of improvisation—has been tremendously important to me recently. If you don’t mind the shameless plug: do pick up Dal Niente’s our George Lewis record when it comes out. This is a way of doing music that everyone should encounter. I find myself noticing that all this music ^^^^^^^ is by dudes, and I regret that there aren’t any ladies on my list; this reflects a complex, long-standing and thorny problem from which I do not exempt myself and in which I have surely been complicit. But I also recognize how much this is changing, and I wonder what it will look like if you ask me this question in 20 years? For more information about Michael Lewanski and his work check out the links below: Personal website: www.michaellewanski.com/ Ensemble Dal Niente: www.dalniente.com/ The following are videos of performances by Dal Niente with Lewanski conducting

What initially got you interested in the idea of composing?

I was probably around 14 years old. A friend, with whom I was also in a band with in some shape or form until I was 27, had the Noteworthy Composer software (remember that thing?). I remember being fascinated by the scrolling score and the fact that no matter what you wrote, the computer played it back. Yes, I’m fully aware that this mentality is not a great idea for, say, graduate students in composition, but to a high school freshman it opened a lot of creative doors. I got the software and pretty much dove in, trying out any idea that came to mind. At the same time, I was in drumline for marching band. We had this book of cadences (most high school/college drumlines have one large, intricate cadence; we had about 20 little ones). Most of these were hand-written (save the ones that our director stole from Ohio State and Ohio University) and were composed by him for our drumline. With equal fascination, I began hand-writing a whole book of drumline cadences. I found a cathartic release in the act of writing by hand; it hasn’t faded. Still today, I get the same calming sensation when I’m sitting in a comfy chair with a blank page in front of me, waiting. These cadences were also the first time I started working with polyrhythm and rhythmic dissonance, though I had no idea that I was doing something along those lines. But, and I still have them around here somewhere, you can see a lot of triplets against 16ths, 5 against 3, etc. So, these pieces pretty much poured out of me all through high school. Sadly, it was during this time that I got the first wrong idea about my music: I had proudly, in my senior year, walked my book of 25 or so cadences and my triptych of mallet trios up to my band director, who was also my percussion teacher, and asked him to look at them. For lack of a better term, he pretty much dismissed the whole thing. A few weeks later, I bounced the idea of being a composition major by him; he gave me the “there’s no jobs in composition” line. These statements didn’t stop me from composing, but they did stop me from showing them to teachers. I wrote a lot during my undergraduate years, and with the exception of my percussion teacher, Ted Rounds, I showed them to no one because I had this weird block, this weird notion that I wasn’t good enough to formally study composition. It took a lot to finally start discussing composition with teachers, and even then it took a few years to finally put my foot down (equally towards myself and others) and cut my own path. We’ve had some conversations about your music in the past, and how it is tied to your interests in visual art and literature. Could you talk a little more about how these other fields influence your music? I doubt I could only talk a little, so get comfortable. Of the two, literature is by far the stronger influence; however, painting is by far the more concentrated and intense influence. What I mean is that when painting’s influence does show up, it is not subtle and it is very immediate, whereas literature’s influence is much more “in the blood” of the my approach to composition. Yes, Rothko is a huge influence and I could easily see someone saying, “You wrote a 90-minute piece for solo piano that covers a few areas of material; obviously there’s Rothko’s influence.” However, I would say that painting in general comes around more in that it gives me permission to toss the sudden change of color here, the visceral, disturbing 10-second thing over there, etc.. What I mean by “permission” is more of a justification to myself to do those things that a teacher (or an audience member or critic or someone who thinks the word “accessibility” means anything to me) may question. With literature, I have to state this: By saying that I am influenced by literature, I do not mean that I am trying to recreate a particular story, emotion, or narrative in a programmatic way. I’m not trying to “set the stage” or “create an image” or portray a plot twist or anything like that. I’m not an author or storyteller, and when someone says, “here’s the part of the piece that portrays the part of the story when X happens,” my first reaction is, “Why? Why are you doing that? The author already made that moment happen in words; who are you to try and recreate it?” In other words, you won’t see me making a leitmotif, something that one has to follow and recognize that “this musical thing means this other extra-musical thing” in order to successfully hear the piece. This discussion could easily tangent into a take-down of programmatic music in general, so I think I’ll stop before I get too snarky. What I take from literature are approaches to form and structure, especially when literature gets nonlinear or circular. Though yes, it’s possibly the most difficult book out there, I love the fact that Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is circular- the first sentence is the back half of the last sentence. Where my mind goes is a curiosity into whatever method and technique Joyce used to turn the story around from going “this” way into going “that” way. Another example is Nabokov’s Pale Fire, which requires the reader to use 2-3 bookmarks at times. My interest in that book is not “the story,” but a curiosity as to what methods and techniques he used to navigate such a terrain. One last example is Agatha Christie. Take the opening of And Then There Were None. Slight spoiler alert, but the secret to the whole mystery is revealed in the first few sentences! My curiosity? What methods and techniques did she use to mask and get around the fact that she gave you the secret so early? I read that story on audiobook during a long drive from Nebraska to Ohio (don’t do that). The story ends and I’m sitting in the car, thinking, trying to remember the whole piece and if there were any clues. Well, the app started to replay the story, and 15 seconds later I realized that I had been told the clue from the get-go. This obviously connects to the circularity of Joyce’s work. I also enjoy the fact that literature can leave things unresolved, can leave loose ends. However, I can see one of your upcoming questions, so I’m going to hold off on this until later. What I will say is this: It’s the way the thing is made that strikes my interest, and I love the different ways that novels and short stories are made. Yes, I obviously understand that there are many different ways that pieces of music are made; however, when a novel (or film, like Pulp Fiction) is nonlinear, it’s clearly nonlinear and the reader or viewer understands the nonlinearity and therefore can place themselves in whatever mode they go to when presented with nonlinearity. That clarity is not so easy with music, and I think (and here’s where I’m apprehensive about saying this publicly because I don’t want to speak for composers, but oh well) composers say, “well if you can’t tell that the piece is nonlinear, why would I write it?” My thinking is “who cares if you can’t tell?” It’s a great way to approach a piece, it places you in a different creative headspace, and it can produce some ideas that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of if you were only thinking, “the piece starts in measure 1 and ends in measure last.” Tarantino makes Pulp Fiction in 1994, confuses the hell out of everyone the first time they see it, and he’s called a genius. Cage makes a form based on chance operations in the 1950s, and people still trash his name (everyone remembers the terrible Huffington blog posts from 2012). More later. Have you always been interested in painting? Is the intersection of music and visual art something that came from your interest in Feldman, or did Feldman come from your interest in art? Yes, I’ve always been interested in painting, but (and here I’m going to change your wording; I hope it makes sense as to why I’m doing so) the intersection of music and other arts came from my interest in Feldman. And my interest in Feldman came from my interest in Mahler. Yep, you read that correctly. When I first starting getting into Feldman’s music and writings, I noticed the recurring theme of painting and rugs. And then I read his essay on Crippled Symmetry (he wrote the essay a few years before the piece) and I saw how the form and structure of rugs influenced the form and structure of his musical material. I then started to ask, “Is there a way to relate the form and structure of novels into the form and structure of my musical material?” At the time, I was reading Joyce’s Ulysses, so I grabbed my copy and grabbed my notebook and started counting. I arbitrarily chose a duration of three hours. I then counted the number of lines in each chapter (not as tedious as one might think; the book tallies every 100 lines or so. It’s based on Homer so it has the layout of an epic poem). I then divided the duration in three movements (the book is divided into three parts of 3, 12, and 3 chapters, respectively) and figured out what the appropriate duration would be. Turns out that if you take three hours and divide into three parts that correspond to the formal division of Ulysses, you get movements of approximately 12 minutes, 126 minutes, and 42 minutes, respectively. I never saw this idea through to an actual piece, but it got me thinking about form and pacing and scale and structure and all of those terms. More on this later. Anyway, to bring it back to your question: My interest in Feldman got me interested in other arts as influence. I chose to go a different route than Feldman, but because I was now curious about all of these other arts, I was now surrounded by all of these other ways of thinking about structure and composition (in the general sense) and approach. It was also at this time that my style started to change in a somewhat drastic way. I think one of the best yet worst things about life is that there’s so much good stuff out there, yet not nearly enough time to fully absorb it all. I hear your music as being very conversational. I don’t notice it in terms of melody/countermelody, but more as voices playing nearly in unison (but not quite), “call/response,” instruments passing a melody from one to the next. Is that something you think about consciously in your compositions? Please email my doctoral advisor, David Gompper, and tell him that you think my music is conversational. Please. My dissertation (which is a piece that is full of negative energy and is a whole other story for another day) was a double concerto, and David’s conception of the concerto is a narrative dialogue between soloist(s) and ensemble, and he kept saying that my music was not conversational and there was no dialogue and all these other negative things. (Don’t email him, but it felt good to read that statement; thank you.) Alright, back to your question. Yes, I think about the act of passing lines and figures across the ensemble in a conscious manner, but I’m not as confident in saying I’m consciously thinking about conversation (so perhaps David was right?). In Essay for Voices, it’s pretty obvious that I was thinking about one human voice transforming into the next human voice, or many voices striking out on their own from and returning to one single pitch. In Piano Trio, it was a conscious effort to separate the strings and the piano, creating an idea of “they do this, they do this again, they do this a third time, and now the piano comments. Repeat.” At the same time, going back to that piece, the fundamental driving force behind the work was one word: sparse. I wanted to make a very sparse piece. The conversation (or dialogue or whatever you want to call it), is secondary. In a lot of my work, the sketches are one or two lines (often in piano score) that then are realized in a contrapuntal way once I get to the notation software. So yes, I guess I’m very comfortable in writing that way - the way of placing lines between voices and seeing where they lead the piece. Some of my favorite music is from the Renaissance (more on that later), and I have an almost unhealthy obsession with canon, so I’m very concerned with how my lines interact with each other. I saw Elliott Carter listed as one of your compositional influences, but I hear a striking difference between your music and Carter’s, primarily in terms of energy and moment-to-moment pacing. Can you talk a little about where the Carter influence comes in your music? I clearly remember being a freshman in college and killing a lot of time in the music library. I loved (still do) reading through scores with a recording. It’s a great way to learn a lot about composing and also how to pay attention! Anyway, I think I randomly grabbed Carter’s First String Quartet one day and gave it a go. Now, as a freshman, I had no idea what the hell I was listening to, no idea how to make sense of it, and ended up being very very confused by the piece. However, for some reason the piece lodged itself in my brain, as if it said, “Hey, remember me? I have more things to tell you.” So, I returned, again and again, trying to figure this piece out in some way. My teachers weren’t much help; I clearly remember a professor putting up their hands in a crucifix when I asked them about Carter, and he was a cellist in a professional string quartet!. So, I kept digging. I remember the first thing about Carter’s music that intrigued me was the rhythmic play between voices, followed quickly by the metric modulations. Being a percussionist, the next stop was obviously the timpani pieces, on which I later did a little bit a research in grad school. The Carter spiral continued with the remaining string quartets, the concerti, and then the giant Night Fantasies - what a piece that is! Have you dug into it? It’ll give you fits!. I’m still following the Carter spiral; his music simply fascinates me on so many levels. But that’s not what you asked. You asked how his influence worms its way into my stuff. Here goes:

Along similar lines, is there any direct influence of Crumb? The meditative pacing, use of nontraditional timbres, and especially the use of the voice in certain works evoke Crumb, but it never loses the identity of your own music. Could you talk about that a little? I used to be a huge fan of Crumb, especially of Music for a Summer Evening and Ancient Voices of Children; I’ll happily admit that the opening of the latter piece is very influential on how I shape a line, both vocal and instrumental (not to return, but the opening cello line of Carter’s First Quartet is, in my opinion, one of the great examples of twentieth-century melody). And yes, we both share elements of meditative pacing, but I think Crumb is a little more clear in his forms than I am. I think my biggest debt to Crumb is how to treat register. Going back to Music for a Summer Evening: There’s a moment where he places a high crotale note against a low perfect fifth in the piano. It’s easy to understand now, but when I was young, I was blown away by the fact that this chord (which I think is something like B-F# with a high F-natural), when played in closed position in the middle of the register sounds dissonant and kind of junky, sounds magical and beautiful when spread out over 5 octaves. Today, I find that I’m very sensitive to register, and I think this sensitivity comes from listening to a lot of Crumb. One thing I took away from your artist statement is the sentence “I often do not intentionally end my pieces, preferring to allow them to stop on their own. I believe that this approach brings a satisfying ambiguity to both the creation of the work and the final product.I” think this is a really interesting and intriguing way to approach form. What led you to take this way of working? This is the “more on that later” from the discussions on literature. Doing those initial calculations on the Ulysses form got me thinking, “Here we have a successful book with a form that works well, but when applied to music it could be considered unbalanced.” I started to question the traditional notions of formal balance and structure; David was very concerned with form, but he wanted us to have traditional balance. After Ulysses I read Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow and Wallace’s Infinite Jest. It was the Wallace that really got me thinking about how we form and shape our pieces. Here’s what I came to: Infinite Jest is over 1,000 pages with 100 pages of endnotes, some of which lead you to other end notes, some of which are chapters themselves. The book, as a piece of literature, is huge; I compare it to the Feldman evening-lengths of 2-3 hours. However, Infinite Jest has three qualities that make it even more complex and difficult: 1. It has no climax, 2. It has no clear ending, 3. It is not a complete story. If the entire tale of Infinite Jest can be represented by a line from 0 to 100, the actual book of Infinite Jest only tells you, perhaps, 10-90 of the story. Or maybe it’s only 40-60. Maybe it’s only a portion of the fifthtieth percent of the story; who knows? We readers, however, don’t mind: it’s a 1,000-page book and we have invested a large amount of our time and are satisfied with the completion of the physical book. This got me thinking, “what would it be like to make a piece that only presented, for example, the middle 80% of the total piece, as if the first 10% and the last 10% were never heard?” Furthermore, I got to thinking, “What if we did this kind of formal design on a piece that is not terribly long, say 10-12 minutes?” From this kind of thinking, you get works like my Piano Quartet, That Does Show Design, Piano Trio, and a lot of the Roman numeral pieces. I don’t hear those endings as the true ending; I simply let them stop. I don’t do this all the time, but sometimes I feel like the piece shouldn’t end, as if it’s not up to me to complete it, but to perhaps take the piece away for now, letting it finish somewhere else (or never at all). Yeah, this approach might sound hokey, but it works for me. The other part of this discussion is that from this approach I started thinking seriously about duration. What are the qualities of “six minutes?” What can you do in a 20-minute piece that you can’t do in a 5-minute piece, but also what can you do in a 5-minute piece that you can’t do in an hour-long piece? What is the personality of 7 minutes, 30 minutes, 180 minutes? Sometimes, in my weirder moments, I would try to pay attention to the passing of time, taking note of what went on in the passing of a certain amount of time. It’s interesting: I came to this approach to form because I felt I had to push back against being concerned with form. Anyway, I really don’t like it when I can tell where I am in a piece, which is funny because one of my favorite things to teach in class is Classical sonata form. I’m like that with a lot of things: I don’t read the backs of books or read book reviews because I do not want to know anything about what might happen. I roll my eyes at a lot of new music concerts when I can hear the “big finish” or the “clear introduction.” If I know a piece is about 3/4ths of the way through, I kind of go on autopilot. I’d much rather work with and experience an elastic, anti-climatic form that doesn’t reveal its entire self until much later, after the piece is over, when you’re rolling it around in your memory. The piece lasts. Coming back to literature, I often think of those characters in Infinite Jest as if they were still working within the story - did Hal ever get better? What happened to Don? Do you have any upcoming projects you’re working on? I do! I finished a three-hour piece for Chamber Cartel back in December and decided to take a few months off to study. In that time, I was asked to write a trio for Soprano, Cello, and Percussion. I’m almost done with the sketches for it, and will be moving on to putting the score together pretty soon. I’m also working on revising a solo double bass piece that I wrote back in my Iowa days; it’s nice to go back to work you’ve done five-six years ago, as you can bring a more objective (and hopefully wiser) approach to the piece. I also have a piece to write for myself; I’d like to make a marimba or multi-keyboard solo in memory of my percussion teacher, Ted Rounds, who passed away last year. Finally, I have this songbook that I told Quince I would be writing for them, but it always seems to be put off to next month (and then the month after, and then…) And the always necessary top 5 - what are the top 5 pieces of music you feel have most inspired you and your music throughout your career? Is it really necessary? Haha. I never know what to say. I’m always apprehensive about these lists, for several reasons. First, what do you exclude? What criteria does a piece need in order to make it into someone’s top five? Second, what about those pieces that you used to really love, but don’t anymore or simply have fond memories of but perhaps don’t feel it’s “top five” worthy? And finally, who is going to judge the list? You know the type: the people who spend more time self-aggrandizing on Twitter than they spend actually working on their craft. These lists are always terrible to make; you see what you’re doing to me, Jon? Haha. Alright, enough complaining. Here goes, with two small bends of the rules:

Listen to some of Anthony's pieces (discussed above) with the embedded soundcloud links below.

To learn more about Anthony and his music, check out his website at https://donofrio-music.com/ Essay for Voices (performed by Quince Contemporary Ensemble) V: oratorio secreta (performed by Chamber Cartel) Piano Trio (performed by Longleash Piano Trio)

You have collaborated with the author and visual artist Webberly Ebberly Finnich (Zachary Webber) on many pieces including your recent work Passion of the Wilt-Mold Mothers for the Quince Contemporary Ensemble. How/when did the two of you begin collaborating, and what are some of the facets of those projects that have kept the two of you working together?