|

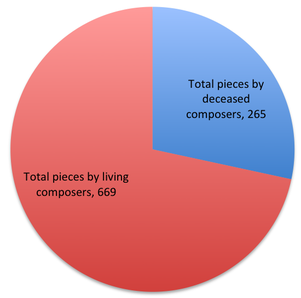

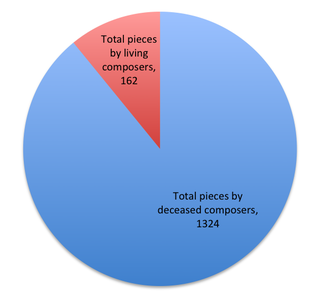

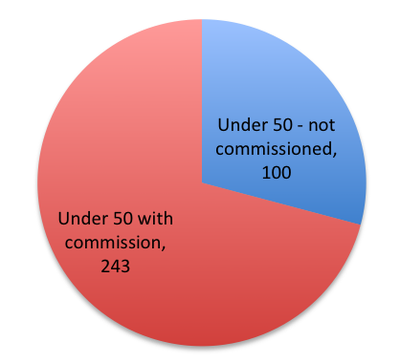

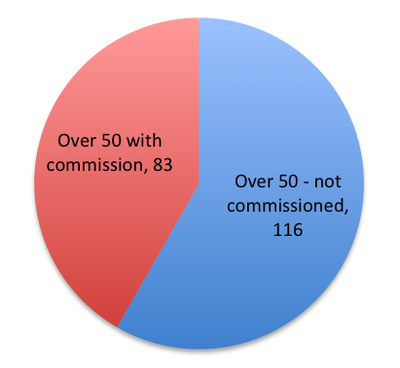

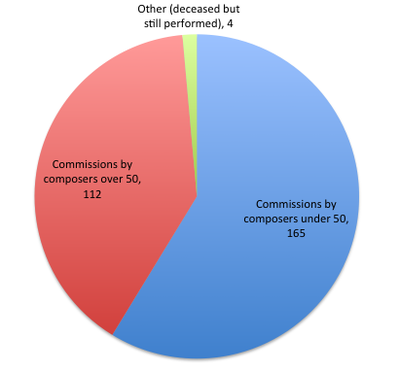

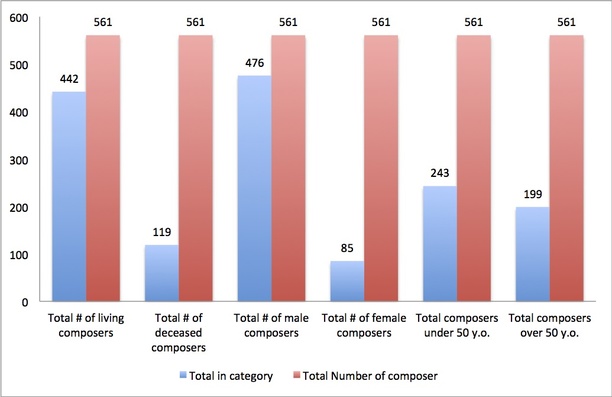

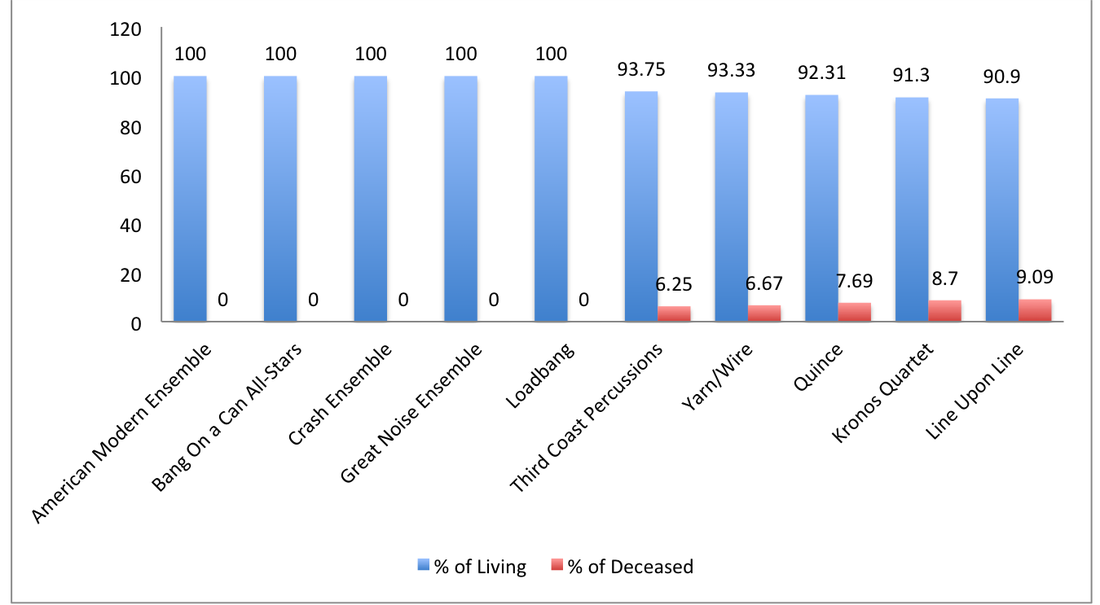

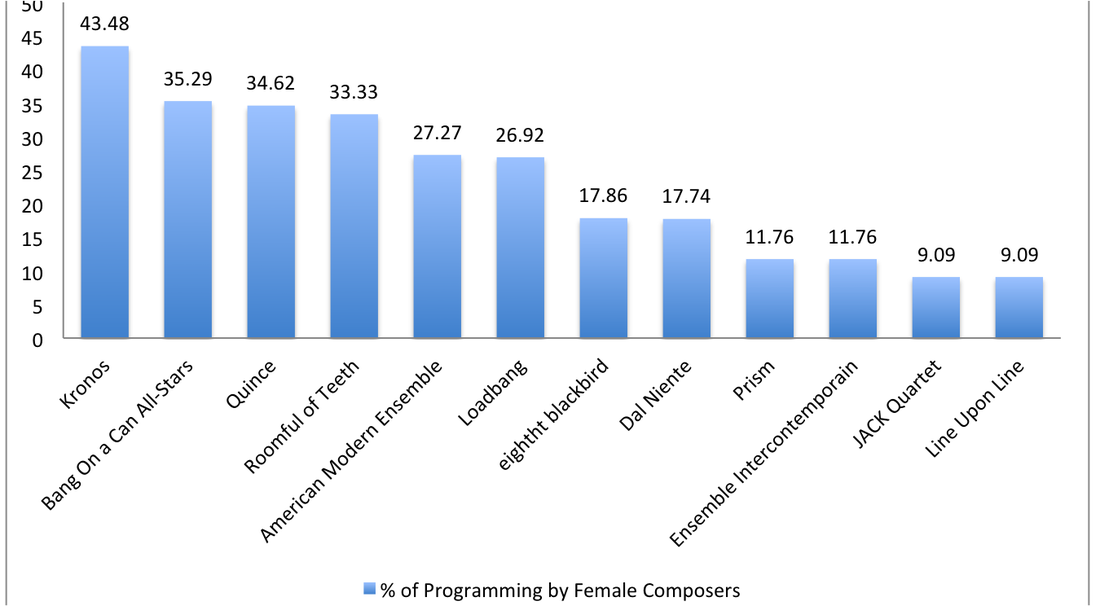

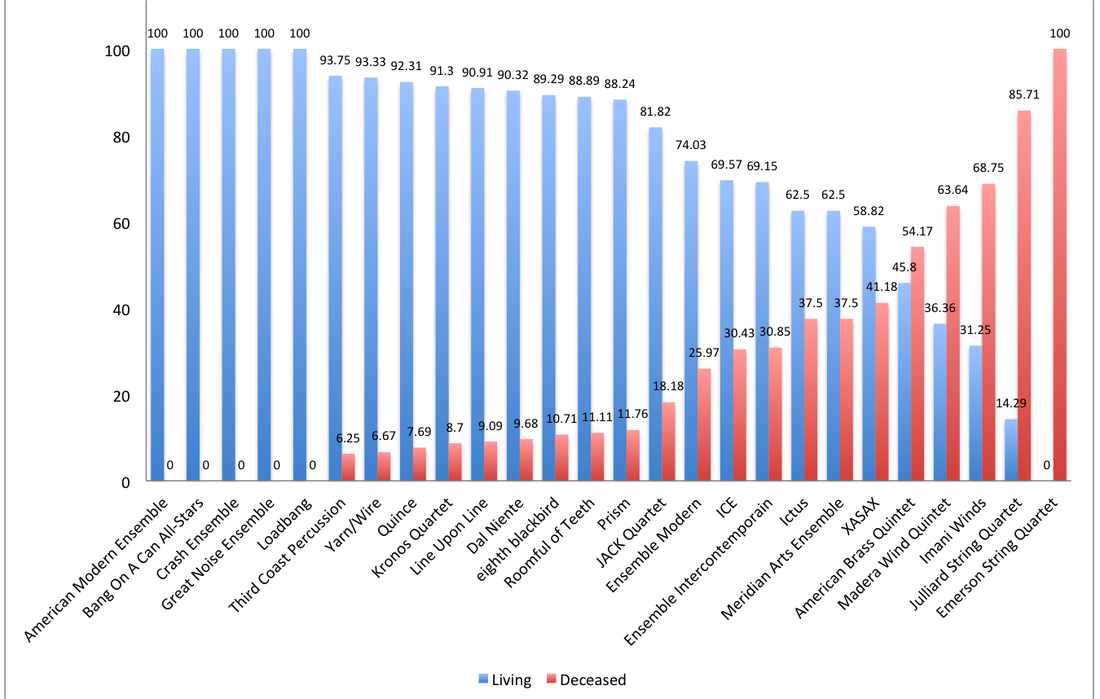

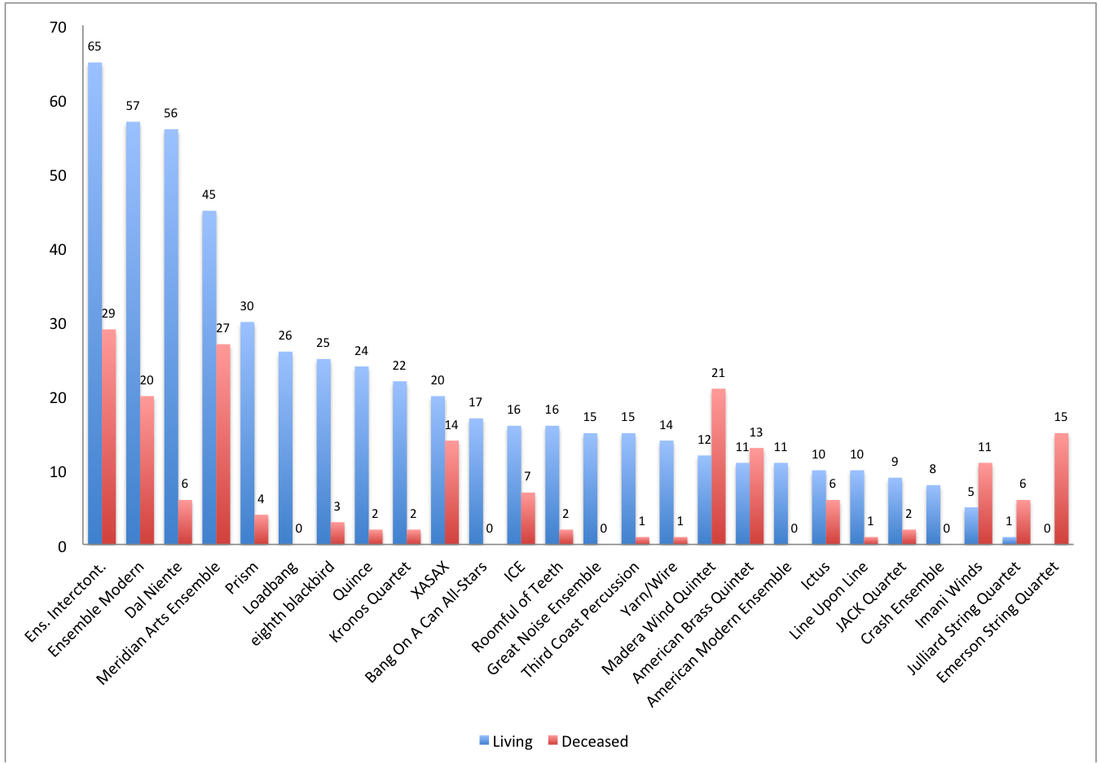

On July 27, Eric Guinivan (the curator of the website Composer’s Circle) published research on programming trends among American orchestras, specifically the number of living vs. deceased composers on orchestra programs in the 2015-16 concert season. The article was very interesting, and while there was nothing surprising in the data Eric gathered, it was good to be able to apply empirical data to the topic. Here’s a quick rundown of the numbers Eric presented: - Living composers account for 10.9% of orchestra programming - 162 pieces by living composers out of 1,483 total pieces programmed in the 2015 16 season - Living female composers is limited mostly to Jennifer Higdon, Anna Clyne, Gabriella Lena Frank and Sarah Kirkland Snider - Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Strauss make up more than 25% (387 pieces) of orchestral programming (Please see the rest of Guinivan’s article for more details. It’s an interesting article and must-read for composers, especially young/emerging composers) Again, this shouldn’t be shocking to anyone who follows orchestra concert seasons. Guinivan’s research confirms the upsetting fact that orchestras and large concert halls simply are no longer a primary support system of the music of today. The numbers in Guinivan’s study combined with this article by New Yorker columnist Alex Ross (and many others like it) paint a dismal picture of the current state of contemporary music. It would seem that audiences, curators, and now even performers are less interested in hearing and/or performing new works by young composers. But is that actually true? I, personally, am not satisfied with that mindset, whether it is the truth or not. That said, Guinivan’s article got me thinking. I knew that there are many outlets for living composers - calls for scores, established new music festivals, start-up festivals, touring chamber groups and soloists actively commissioning new works, artist residencies, etc. After making a long list of opportunities and outlets for younger generations of composers I decided to do my own version of Guinivan’s study. I gathered programming information for the 2015-16 season for various chamber ensembles, primarily American chamber groups. I then gathered the total number of living and deceased composers per ensemble. I calculated the number of living composers, deceased composers, male, female, total number of works by a composer and total number of commissioned works by each composer. After gathering this data for each ensemble I made a database of all the composers to take a look at the numbers without dealing with the issue of duplication (in other words, the database calculations would only count a composer once even if they appear on the roster of multiple ensembles). Then there was the issue of scope. Chamber music is a very broad category. To get a good sampling of (nearly) everything that goes on in chamber music I broke ensembles up into the following categories: - Mixed ensembles of more than 8 players (8 ensembles) - Mixed ensembles of 4-8 players (4 ensembles) - String quartet (4 ensembles) - Saxophone quartet (2 ensembles) - Wind quintet (2 ensembles) - Percussion ensemble (2 ensembles) - Brass quintet (2 ensembles) - Vocal ensemble, mostly a capella (2 ensembles) The following is a list of all of the ensembles used for this research. American Modern Ensemble * American Brass Quintet * ^ Crash Ensemble * Meridian Arts Ensemble + Ensemble Dal Niente * ^ Emerson String Quartet Ensemble Modern Julliard String Quartet Ensemble Intercontemporain Kronos Quartet Great Noise Ensemble Imani Winds * ^ Ictus Madera Wind Quintet + ^ International Contemporary Ensemble * ^ Prism Quartet * + Bang-On-A-Can All Stars * ^ XASAX Quartet + eighth blackbird * ^ Line Upon Line Percussion * ^ Loadbang * ^ Third Coast Percussion ^ Yarn/Wire * ^ Roomful of Teeth * Quince Contemporary Ensemble * ^ JACK Quartet * * = ensemble was contacted and directly provided programming information + = ensemble repertoire list and past programs used to collect data; programs subject to change during season, full rep. list is used throughout concert season ^ = ensemble does residencies at schools/universities during concert season and performs student works not listed on regular concert season So what did the numbers look like, you ask? Here’s a short breakdown: - 934 total pieces by 561 composers - 443 out of 561 are living composers (79%) - 118 deceased composers (21%); compared to 89.1% of orchestra programming - 36 composers deceased within the last 25 years - 476 male composers to 85 female composers - 15% female composers. Still a terrible number In short, the numbers for chamber ensembles is totally opposite of what Guinivan found to be the trend for orchestras. The only number that isn’t drastically different is the number of female composers. While 15% is an embarrassingly small number (and poor representation) of female composers, what is important is that the 15% represents a total of 85 female composers. Compare that to a little more than 4 in orchestral programming. The two graphs below show the difference in programming living vs. deceased composers for the chamber groups in my study and the orchestras in Guinivan’s study. I was really excited by the results on a preliminary compiling of all the data, so I decided to dig a little deeper and see what else I could uncover. Here are a few more tidbits: - 934 total pieces programmed - 265 by deceased composers (28%) - 669 by living composers (72%) - compared to 162 by orchestras (who are also programming roughly 549 more pieces than chamber groups [60% more music than chamber groups]) - 281 commissioned works - 30% of total programming is made up of commissions - Loadbang, Yarn/Wire, Crash, Great Noise Ensemble, Bang-On-A-Can All Stars create most of their programs from commissioned works due to the nature of the instrumentation - 41% of music by living composers is made up of commissions Those are some pretty great figures if you ask me. It seems from these numbers alone that the chamber groups are not only supporting the music of living composers, but they are actively commissioning new works! The numbers for commissions got me thinking even more about who exactly are these ensembles commissioning? Bill Doerrfeld wrote and article for New Music Box called “Ageism in Composer Opportunities” about the limited opportunities made available to aging composers, and my research made me wonder if I could find anything to confirm or deny Mr. Doerrfeld’s claims. Here is what I came up with: - 443 total living composers - 243 composers under the age of 50 - 200 over the age of 50 - 323 pieces by composers under the age of 50 (34.6% of total programming!) - 101 living composers with multiple pieces programmed - 281 Commissioned works - 133 composers under 50 with commissioned works - 165 total commissions by composers under 50 - 100 total composers over 50 with commissioned works - 112 total commissions by composers over 50 4 commissions by deceased composers; pieces still part of ensemble repertoire and programming catalog Well it would seem that if you’re a composer under 50 living in America and actively writing chamber music then you’re in a pretty good place. That isn’t to say that the state of things for composers over 50 is necessarily awful, but there is a slight tilt toward favoring programming and commissioning younger composers, at least by the ensembles who took part in my research. The graphs below give you a better look at this information. The following graph shows all of the information gathered in the master database of composers The last thing I decided to look into were the numbers for the ensembles themselves instead of looking primarily at the master list of composers. The following is the breakdown of some ensemble data: Top 10 Ensembles programming living composers

Top 10 Ensembles for programming women

The following graphs show the percentage of living and deceased composers broken down by ensemble (top) and the total number of pieces programmed by living and deceased composers divided by ensemble (bottom) So what did I take away from all of this? Well, first, the state of new music is not in dire straits as I’ve always believed. The chamber ensembles sampled for this research are not only actively seeking out living composers, but they are thriving on that music. In addition to that they also favor music by younger generations. While this may be upsetting for the older generations of composers, it is comforting (at least for me) to know that so many talented ensembles are giving the composers of my generation a voice. Something else I found interesting while poring over the numbers is that many of these ensembles perform more frequently at venues other than concert halls and universities. While there is a large number of university performances, it seems that many smaller ensembles are seeking out new venues to share music with people. Some are performing at nightclubs, some at libraries, art galleries, outdoor spaces, and other non-traditional venues dedicated to the performing arts. What this says to me is that these performers are seeking new audiences - and apparently finding them if this trend is ongoing. A conversation I often have with my friends and colleagues is how to get our music to more people. How do we fill up out concert halls with a packed house? How can we bring our art to the communities in which we live? I think many of these ensembles have found the answer, and that is to bring the music to the audience. So much new music (especially experimental new music) is more fitting in a more relaxed setting than a concert hall provides, and people might be more inclined to sit and listen to a concert of challenging music if it is presented to them in an environment where they already feel relaxed and comfortable. I have more I could say on the topic, but if you want to know more you can check out my discussion of the Omaha Under the Radar Festival this past summer. I also noticed that the more “traditional” ensembles (string quartets, wind quintets, brass quintets) are programming more music by deceased (some long-deceased) composers. And why shouldn’t they? They have a much larger catalog to pull from and audiences have come to expect certain things from these ensembles. That isn’t to say they are not supporting new music, just that their numbers may lean more in favor of playing classic pieces of the genre in addition to new works and commissions. Also, my research was done with a very small sample, and the numbers might change if we were to consider, say, 100 chamber ensembles. Maybe the numbers would show stronger favor for deceased composers? Though, I would like to think that they would change very little. The ensembles that I chose are some of America’s (and Europe’s) top performing chamber groups right now. They are a benchmark of new music and are the trendsetters for new music worldwide. And it seems that trend is one that leans in favor of supporting living composers and encouraging the creation of new works in hopes of spreading contemporary music to the world. Thanks for reading. Please feel free to share any thoughts or comments below.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The "Direct Sound" Page is dedicated to general blog posts and discussions. Various topics are covered here.

Full Directory of Articles |