|

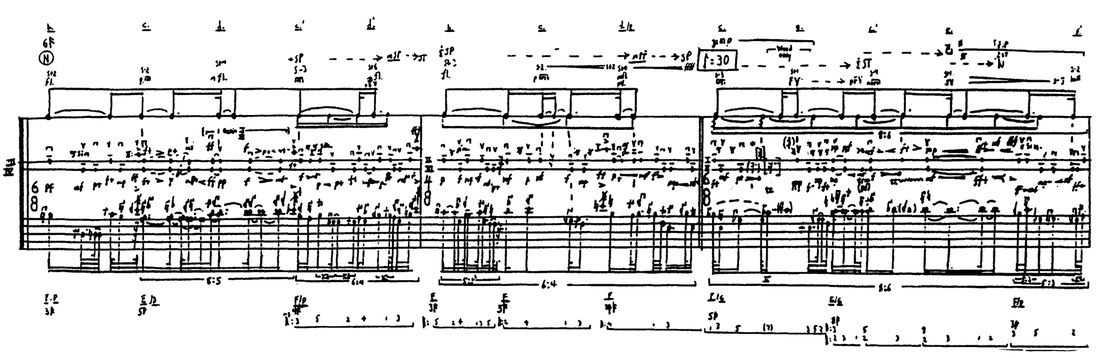

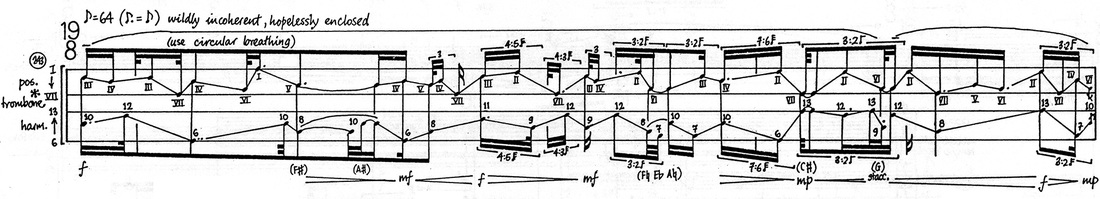

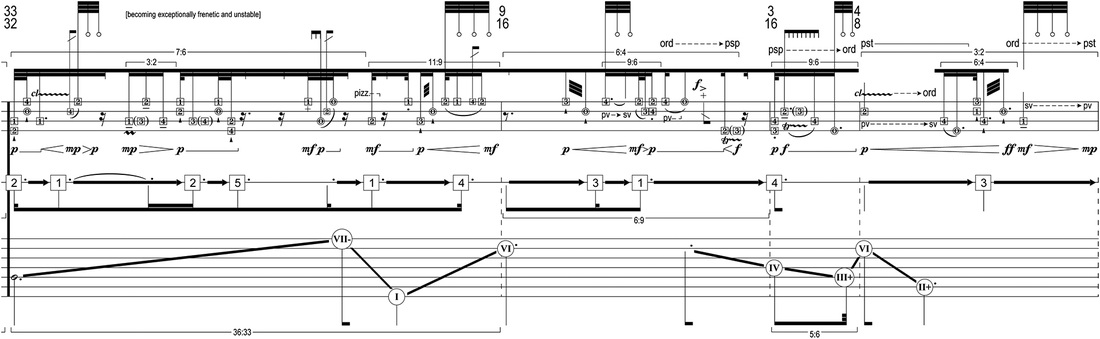

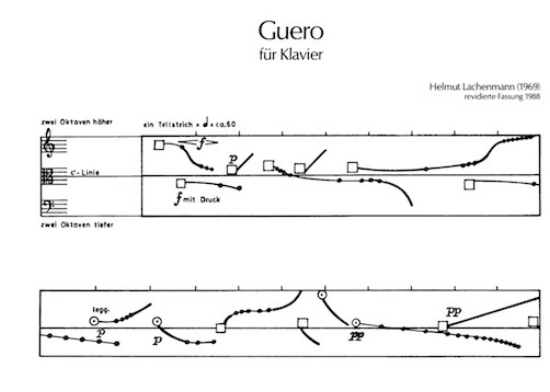

This week I would like to talk about something that has been on my mind a lot recently, that being the practice of notation of physical gesture. What does it mean to notate physical gesture, you might ask. Let’s think for a second about what we’re looking at when we read music. We see a line of musical symbols displayed as rhythms, pitches (sometimes), dynamics, articulations, etc. This is a representation of what should result from the physical actions of the performer playing his or her instrument. But what if, instead, a score provided instructions for how the performer should play as opposed to what the performer should play? This is the central idea to notating physical gesture. The first time I came into contact with this type of notation was with Frank Cox’s Recoil for solo cello. In Recoil, Cox notates the desired pitches and rhythms, but not as a single line of music. He notates the physical motion and gesture of the performer through a multi-staffed scored in which the performer realizes all staves simultaneously. The staves represent (from top to bottom) 1. bow pressure/position (right hand only), 2. the string(s) which should be played (right and left hand) and 3. the pitches fingered with the left hand (left hand only). Each staff is rhythmically independent, resulting in a contrapuntal relationship of physical movement, as opposed to a contrapuntal relationship of separate distinct voices. I find this method of notation very fascinating. There is so much physicality to playing a musical instrument, but as musicians (specifically in the Western art music tradition), the instructions we look at - the score - provides us with the sonic result, but not with instructions on how to create that result. Cox has taken a different approach, a prescriptive rather than descriptive approach to his notation in Recoil. Other composer including Helmut Lachenmann, Klaus K. Hubler and Aaron Cassidy also practice their own methods of this form of notation. With all of these composers (among others interested in this notion), the concept of physical gesture of the performer - the actual motion required to make the sound - is what is communicated to the performer. It is the performer’s job to then communicate the resultant sound to the listener. The following are examples of scores that use this method of notating gesture over sonic result: An initial question one might ask when looking at these scores is why choose this method of notation over traditional notation. What does the composer gain from taking this approach? What does the performer gain from this notation? Does the notation really accomplish something different than traditional notation, or does it just serve to complicate the learning process and performance experience for the performer? In addition to providing the performer with a completely foreign notational concept, the counterpoint of the physical actions is incredibly intricate and the presentation of the score is often highly complex and difficult to decode. So, why do this?

My response to these questions is that music of this nature really can’t be notated any other way. Take a piece like Recoil, in which the bow pressure and direction have their own rhythmic line while the left hand is changing pitches with different rhythmic patterns, often completely separate from bow changes. At the same time the performer is asked to play the same pitch patterns on different strings. To notate the resultant sound of those actions would be close to impossible. Even if one were to notate that resultant sound, would it be less complicated than Cox’s notation? What if the desired result is impossible to notate? Richard Barrett’s piece EARTH for trombone and percussion (shown above) uses a similar notation that Cox uses in Recoil. The trombonist reads multiple staves that display slide position and the partial to be played. At certain times the slide position and partials do not align rhythmically, just as the left and right hand don't always align in Recoil. How could a composer notate the sonic result of that kind of physical action? More importantly, how would the performer know exactly how to produce that resultant sound? In this situation, there is no clearer way to notate the music than by describing to the performer the physical actions necessary to produce the music. Another argument in favor of this type of approach is that all notation is really just a system of abstract symbols. We can attach any meaning we want to those symbols and realize them in any fashion we feel necessary in order to achieve our artistic goals.. In the situation of Cox’s Recoil he uses traditional notation, and prescribes a new meaning to what the rhythms and symbols represent, as does Barrett. Lachenmann takes a fully graphical approach with his piece Guero (shown above), wherein the graphic images represent the motions of the player and position of the hands on the keyboard. Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory (shown above) uses both standard and graphic notation, all of which is representative of movement rather than sound. Really, this is a similar approach to tablature for stringed instruments, which uses numbers to represent fret positions and staff lines to represent strings. Some composers, including Aaron Cassidy, refer to their scores as using tablature notation. Tablature also does not provide the performer with the resultant sound, but instead with the physical placement and motion of their hand(s). Going back to the opening paragraph of this post, the performer is instructed how to play, not what is heard. There is a lot more that can explored concerning this topic, and other types of nontraditional approaches to notation, too, but this post is intended to just be an introduction on the topic. If you’re a musician interested in this method of composer/performer interaction, I strongly encourage you to explore some of this music through listening, analysis of these pieces, and even try to play some of these works if you’re feeling adventurous! If nothing else, it will give you a new perspective of all the physical action(s) of performing music, even something as straight-forward as a simply notated melody.

3 Comments

tomek

11/19/2015 06:27:21 am

Thanks for this article. Do you know of any examples where the gesture notation was done on some other than paper medium? It would make sense to record movement/gesture on video emphasizing (closeups) along with classic score material.

Reply

Jon

11/19/2015 07:37:47 am

Good question. I only know of one piece that utilizes something other than a paper score for the gesture notation. The composer Michael Baldwin composed a piece in 2014 called "this is not natural" for horn, contrabass and piano. I don't know a lot about the piece in detail, but from what I understand the performers record themselves on video performing a very short gesture. They then play the video back slowed to an extremely slow speed and the three performers move at the pace of the video. The result is the original recorded gesture slowed to a snail's pace which causes a lot of subtle and nuanced effects and timbres to come out of the texture. Here's a link to the video https://vimeo.com/91071584 and here is a link to an article in the Rambler that Michael did concerning this piece https://johnsonsrambler.wordpress.com/2014/07/18/contemporary-notation-project-michael-baldwin/

Reply

Hi Jon, Leave a Reply. |

The "Direct Sound" Page is dedicated to general blog posts and discussions. Various topics are covered here.

Full Directory of Articles |